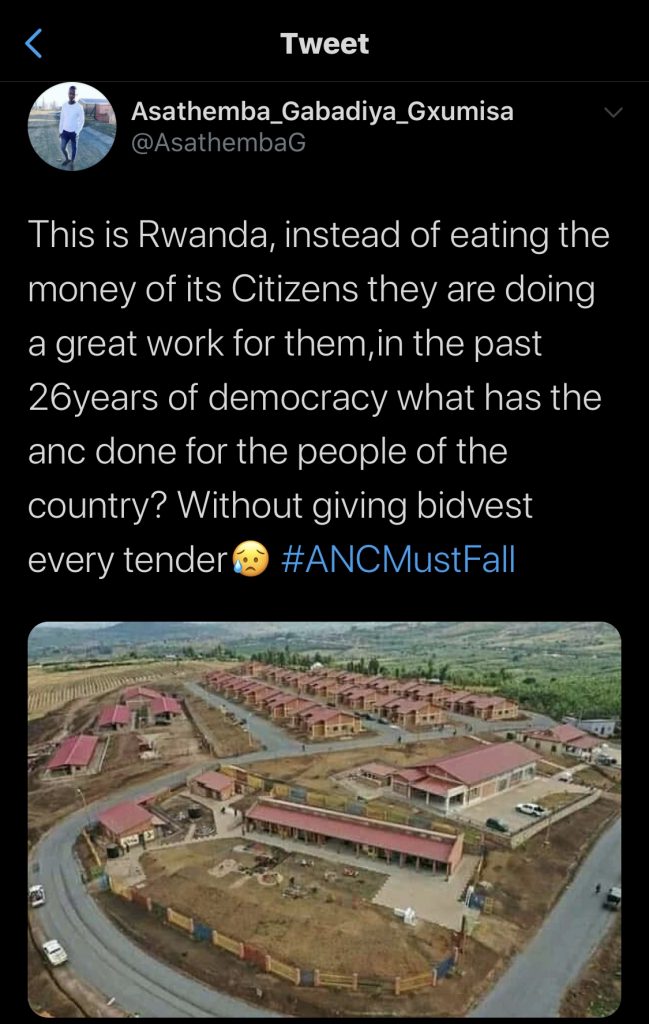

On Saturday, the 4th of July 2020, the hashtag #ANCMustFall was trending on twitter. The drive behind the #ANCMustFall twitter hashtag was young South Africans, seemingly desiring an end to African National Congress (ANC) rule governance. As the 100th Day of Lockdown descended upon us, I had been thinking of how we need to continuously work towards a just future South Africa.

The emergence of the #ANCMustFall hashtag was not surprising, given the horrible state South Africa is in. A horrible state of things brought into even sharper focus by the impact of the coronavirus crisis. A sharper focus that made it even harder than usual to look away. What we have seen during these past 100 days is the consequences of corruption, mismanagement, racketeering, nepotism, and reckless spending of the past 25 years.

Over the past 100 Days of Lockdown a light was shone on some of the most dreadful aspects of post-apartheid South Africa. Multiple municipalities in the Eastern Cape are bankrupt and dysfunctional and cannot provide the most basic of services to the people. Livingston Public Hospital located in Nelson Mandela Bay (Port Elizabeth) failed a safety audit; all around the country young people experience evictions, hunger, and heartbreak; the North West Health Department was placed under administration two years ago, and it is still experiencing problems; Collins Khosa was assaulted and murdered by state law enforcement and no one has been arrested for his murder; the school’s feeding scheme run by the Department of Basic Education has been chaotic since the start of the COVID-19 and this was/is an important source of nutrition for thousands of children across the country; Nelson Mandela Bay made headline news as the maternity services were said to be near collapse with pregnant women sleeping in hospital corridors; the Unemployment Insurance Fund has been a source of pain and frustration as many people battle to access the funds for basic living; the City of Cape Town was involved in a series of evictions of homeless people, the eviction of a naked man while he was taking a bath in his home was the most horrific; SASSA offices have been operating sporadically, in Cape Town the SASSA offices were closed for a whole week; there has been reports of food parcels being stolen, and not reaching their intended recipients; in KwaZulu Natal there were reports of missing PPE’s and then they somehow reappeared again; people are complaining about the price of food during the lockdown, the prices of food have gone up while people’s income has disappeared. These are just some of the things that have come out of the 100 Days of Lockdown, and for many of these issues there’s no ready solution. South Africans will have to “make do” and “ride it out” as the corrupt and inept state drags itself forward.

The South African state is ill equipped to deal with the coronavirus. Granted, this is not unique to South Africa, many countries around the world have been battling to get a handle on the virus outbreak. What is evident is how the coronavirus and its effects are made worse by the lack of service delivery, and dilapidated infrastructure that has in part been caused by corruption and mismanagement of state funds. In other words, public health care in South Africa was broken before Covid-19 arrived. So, the state is not just ill equipped because this is a novel virus that came out of nowhere, it is ill equipped partly because state run hospitals, which are the hospitals used by the majority of the population, have been run down by mismanagement. They are unable to function properly under “normal” circumstances, when there is no virus.

No matter where you look, in all directions, the ANC-led government is RESPONSIBLE for the hunger people are experiencing, the lack of inefficient rollout of Unemployment Insurance Fund, the collapse of public health institutions in certain parts of the country, and the collapse of the economy.

Granted, the ruling government inherited apartheid legacies and structures and these are hard to change overnight. But the ANC-led government has had more 25 years to fix some of the most basic infrastructure and services that were legacies of apartheid, particularly in health and educations sectors. Furthermore, stealing state funds meant for service delivery through embezzlement and corruption in 2020 cannot be blamed on apartheid.

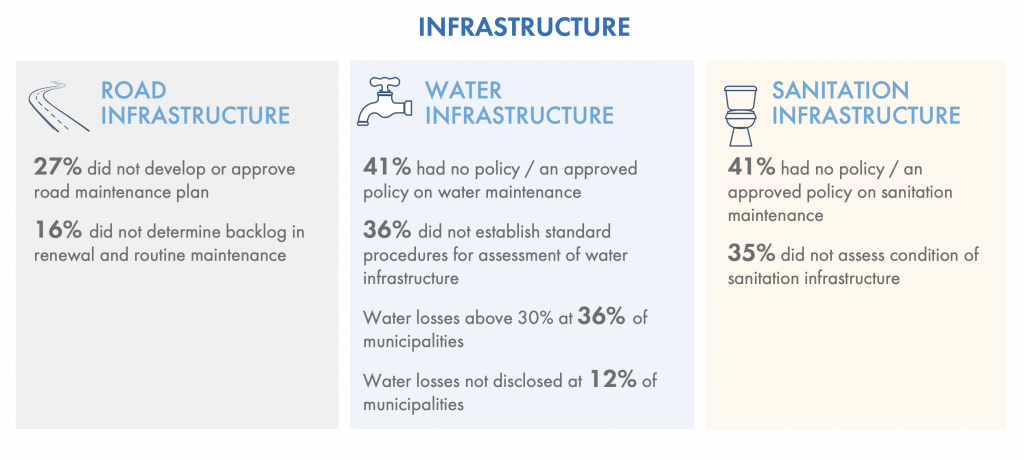

The consolidated general report on the local government audit outcomes for the 2018-19 cycle demonstrates astronomical theft, mismanagement, and corruption in ANC-led municipalities around the country. The findings of this report cannot be blamed on apartheid. The ANC-led government needs to take responsibility and be accountable to citizens about the horrible theft of state resources.

Over the past 100 Days of Lockdown, it has been heart-breaking to read the stories that appear in the media, the stories shared on social media networks, and personal stories of close relatives over the phone.

After the 100 Days of Lockdown we have had in South Africa, the hashtag #ANCMustFall is really an appropriate response. I am angry over the state of things. Many people, as demonstrated by the #ANCMustFall hashtag are also angry with the state of things. South Africa deserves better than the corruption, mismanagement, and the lack of accountability from the ANC-led government.

While I agree with the sentiments of the hashtag #ANCMustFall, if we are to create the kind-of country we deserve, then we need to be strategic, we need to build a movement. As I shared in the piece Notes Towards A Better World: 100 Ways to Better South Africa, a youth-led political movement is what South Africa needs. Like many have pointed out in the #ANCMustFall tweets, the elders in the ANC are out of touch, and are unable to govern.

Seeing that the youth of South Africa will inherit the country, it makes sense that they take charge of moving South Africa into the future. Furthermore, the youth of South Africa have a history of being at the helm of revolutionary change and June 16 is a testament to that as an annual celebration of South African youth power and determination.

While the #ANCMustFall hashtag is a good start, a youth-led movement for a future South Africa will need to be strategic in unseating the ANC-led government. The ruling government will not be defeated without a well thought-out, clear, and strategically executed plan. There was a funny #ANCMustFall tweet that jokingly said they were going to hide their grandmother’s ID book in order for the grandmother not to vote for the ANC. I don’t condone the hiding of people’s ID documents, but there’s a lesson here. Statistically, older citizens have a higher voter turnout than young people. This means that the first order of business in a youth movement for the future of South Africa would be to ensure that young South Africans go and vote. By “young South African” I am referring to anyone and everyone eligible to vote born after 1980.

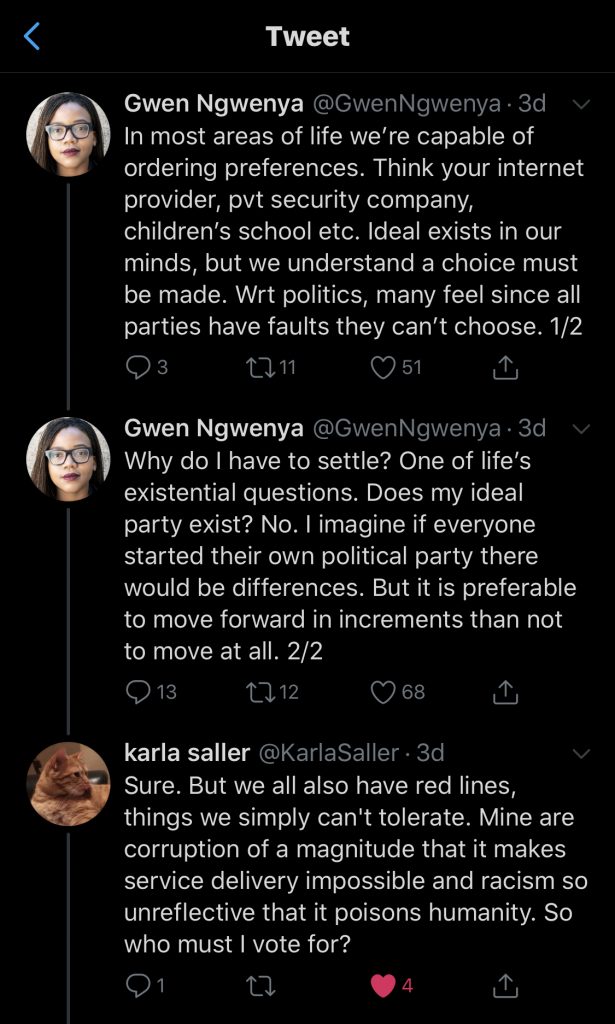

Once we have mobilised a Youth Movement for the Future of South Africa, we will need to think about who to vote for as we try to carry out the #ANCMustFall hashtag. This is and will be the greatest challenge to the youth movement, finding, or grooming, the kind of leaders we envision for the future South Africa. I saw a twitter correspondent this past week between Gwen Ngwenya and Karla Saller, where Saller was arguing that it’s difficult to find a good candidate, and/or a good party to vote for in South Africa. The choices seem to vacillate between political parties with histories of corruption, and political parties with racists policies and philosophies. As I said to Saller, many South African voters, myself included, are caught between the devil and the deep blue sea.

This is a conundrum that a youth-led movement can possibly solve. But in order to solve this conundrum, let’s say for 2024, a well thought out plan would need to be put in place, with strategic long-term goals. We need to create something, a future, a possibility that South Africans can believe in again. This can be achieved with a buy-in from the majority of young people, and those who are interested in this new future South Africa.

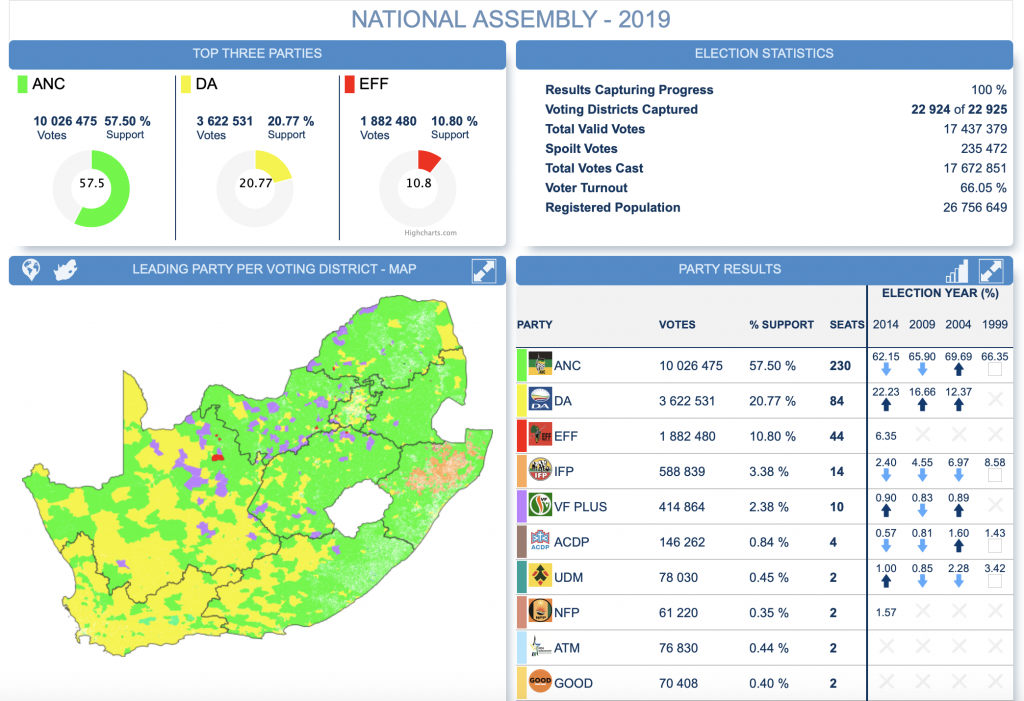

Many conversations about change in South Africa often cannot get past the power of the ANC. What many don’t realise is that over the years the ANC has been losing voters, receiving less votes with every election. With a concerted effort of massive youth mobilisation, the fall of the ANC can be achieved.

Recently, Doug Coltart wrote a piece called Rule of law must first be strengthened by people power, for the Mail and Guardian. In the piece Coltart argues for the need for grassroot movements in South Africa because state institutions are fundamentally broken. Coltart argues that, “To strengthen the rule of law, we first need to focus on strengthening people, not institutions. This involves the difficult, dangerous and often unglamorous work of grassroots organising that empowers citizens to act through informal channels outside of established institutions.” Furthermore Coltart states that “Building people power starts with opening citizens’ minds to a different type of society and a new way of doing things.”

With a strong youth movement that mobilises young people to actually register and vote, real change can be created. Through mobilisation, real opposition to ANC rule can be created. Often, when we think about political change, or challenging the dominance of the ANC, we see winning as impossible because it has not been done successfully before. I think this kind of thinking is what has led us to where we are as a country because we don’t bother to challenge the status quo. With a strong and coordinated youth movement we can provide a serious challenge to contemporary party politics that have been disastrous for poor people.

As the youth of South Africa, we have the power to change the course of this country.

Changing the current political climate, through a youth-led movement is necessary for the future of South Africa.

As I write this I am listening to the sounds of Zoë Modiga, particularly the song “Abantu” where she says, “Uzojiki izinto, uzojiki izinto.” Her album Inganekwane, and particularly this song, “Abantu” is exactly what this pivotal moment in South Africa calls for. In writing this, it is my hope that we would heed Zoë Modiga’s call and sijike izinto.