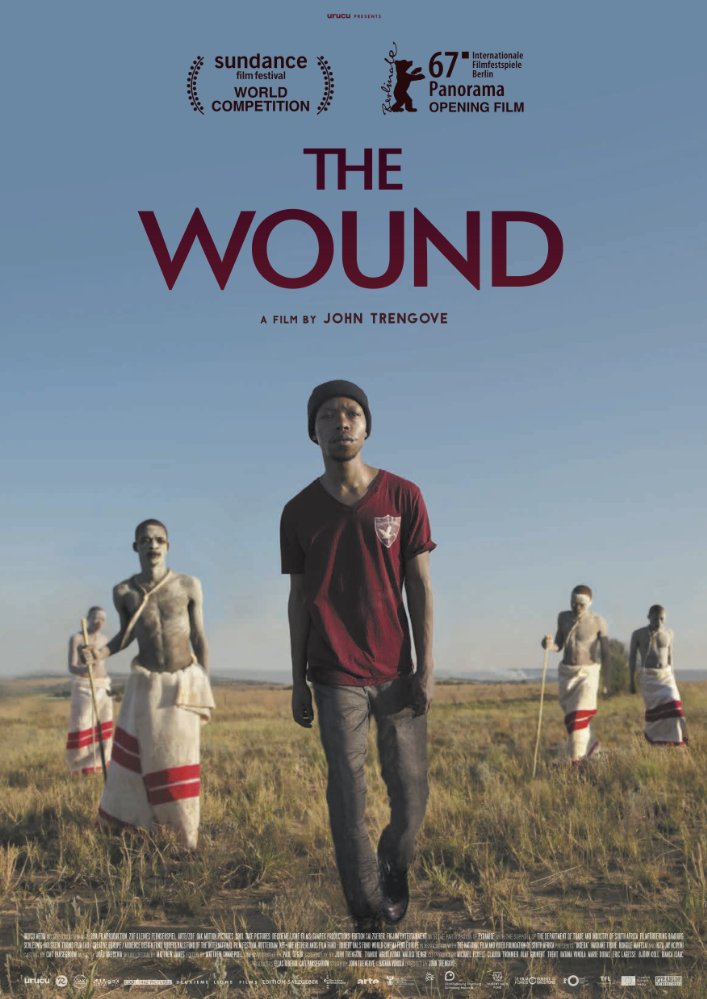

Inxeba (the wound) is a groundbreaking movie. It is a combination of artistry, emotional depth, and a serious engagement with a difficult subject, often taboo subject, that makes Inxeba probably the best South African movie in 2017. Nakhane Touré who plays Xolani, Bongani Mantsai who plays Vij, and Niza Jay who plays Kwanda are amazing in their individual portrays of the characters, but are explosive as a trio. In this movie you are confronted by the violence inherent in the construction of Xhosa manhood through circumcision. You are confronted with the pain of Xhosa men who are unable to claim and live out their sexualities. After watching this movie I am even more convinced that the subject formation of Xhosa men is a violent process. Also, the process of man making is lonely.

Inxeba is a movie about the experiences of queer Xhosa men when they go to initiation school. It is a movie about the intersection of sexuality, manhood, tradition, and desire. The movie exposes the ways in which manhood, particularly Xhosa manhood, in this case, is rigidly policed by other men. You are confronted with the consequences of a homophobic culture and society where men are unable to claim and live out their sexual desires for each other.

I went to go watch the movie with my queer friends. While we were watching the movie, we laughed out loud at certain moments in the movie, we gasped, we looked at each other knowingly, we made faces to each other. We were seeing ourselves in the movie. When we spoke after the movie, we all agreed that watching the movie was like seeing our younger selves on the screen. Stories that centralise the experiences of black queers matters because there is very little of our reflections in South African stories. These stories also matter because they enable us to publicly engage in conversations about culture, manhood, and sexuality. These stories create platforms that enable us to have a conversation about what it means to be a man in post-apartheid South Africa. What is the role of culture in 21 century South Africa? Stories like these enable us to ask questions about the process of “constructing a man.”

For me, this movie has resurfaced questions I have often debated with my and myself and my friends, like, how do you make a man? What makes a man a man? Who can be a man? Who says who can be a man? As a queer person, I have had to engage these questions all my life because my manhood was always under scrutiny. And many men have noted my “failure” at performing manhood. In one of the scenes in the movie, the initiates are circumcised and the person who does the circumcision asks the recently cut boys to shout “I am a man.” There is something powerful about this pronouncement. Uttering these words just after you have been circumcised cement Xhosa culture belief that you are only a man once the foreskin is gone. It is also bizarre that the foreskin is what separates “boys” from “men.” But of course, I am being simple, for I know that it is not foreskin per se that is at the heart of this practice but the pain you endure as you recover from circumcision.

At one point in the movie, the father of the queer initiate addresses the caregiver, giving him instructions to be “firm” with the queer kid. The father complains that his son is “too soft” and then he goes on to blame the mother for the boy’s softness. It is ironic how the supposed “failure” of the son to be “manly” is blamed on the mother, not the father. Which of course, begs the question, had the son succeeded at being “manly”, whatever the fuck that is, who would get the kudos? I’ll go on a limb here and say that the father would praise himself for having raised a “man.”

The father distances himself from his son, which is very revealing of the relationships many queer boys, particularly effeminate queer boys, have with their fathers. In this then manhood is associated with not being “soft”, not being a “mama’s boy”, and if you are soft, you need to be toughened up. In Xhosa culture, a man is made through pain. The ability to withstand immense pain is intricately tied to Xhosa masculinity. This is not unique to Xhosa culture, of course, it is part of patriarchy in many parts of the world. When I think of manhood construction through pain, when I think of this movie, I am reminded of bell hooks when she wrote:

“The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves. If an individual is not successful in emotionally crippling himself, he can count on patriarchal men to enact rituals of power that will assault his self-esteem.” – bell hooks

The accuracy of bell hooks in describing the violence of patriarchy on men is chilling. bell hooks speak to the detrimental effects of patriarchy on men. She speaks to the value of feminism for men. She speaks to the need for men to fight patriarchy because it damages men. This quote speaks to the destructive ways in which the characters portrayed in Inxeba conduct themselves, towards themselves and then to each other.

I was incredibly moved by the scene where the men are asked to verbalise and claim manhood after they are circumcised. The “I am a man” scene is interesting to me on many accounts. The queer initiate Kwanda, played by Niza Jay is the last initiate to be circumcised. He is then also asked to announce the statement “I am a man.” In his effeminate voice, Kwanda repeats the phrase. It is the first time we hear Kwanda speak, and the voice is a “giveaway” that he is queer. Even my friends and I looked at each other in the theatre when Kwanda spoke. After Kwanda says the phrase “I am a man”, the man who performed the circumcision asks him to repeat the phrase, and Kwanda does. Kwanda is the only initiate who is asked to repeat the statement as if he was not heard before but most likely because he was not believable the first time around.

The “I am a man” scene reminded me of myself in many ways. When I went to initiation school, none of the boys who were initiates with me knew who I was. I was thrust into a “man’s world”, a world I had never really been part of in the ways the other boys were. In many ways, I am still not part of that world. I was acutely aware of violent homophobia when you are queer in the company of other men. Men often perform homophobic violence in the presence of other men, in conversation with other men. When I arrived on the mountain I knew that my survival depended on being a wallflower. The problem, of course, is that my personality does not lend itself to be a wallflower. I had decided that I will say as little as possible, keep to myself, and avoid any contact or conversation that would “out” me. It was only on the second day that I realised my plan not to be “out” had failed when another initiate mocked me by mimicking the way I had said the “I am a man” phrase after circumcision. My effeminate voice had betrayed me. Now my girly intonation was being used to mock me. The violence and shame I felt in that moment still makes me well up. And it’s been over a decade now.

The relationship between Xolani and Vij is complicated. They are both in the closet, and they annually meet during “circumcision season” on the mountains. Vij has a wife and children. Xolani lives a lonely life. Xolani’s loneliness is haunting. What Nakhane Touré does with this character is nothing short of brilliant. Xolani really only goes to the mountain to be with Vij. Considering the homophobic context they live in, and their own policing of their desires, it’s an impossible situation. The homophobia is not only coming from their society and culture, it is also internalised by the men. The two men share intimate moments with each other, but there’s also violence in their intimate moments. It’s as if their desires for each other has to be mitigated by violence.

There are two moments in the movie where we see the complex intimate yet violent interaction between Xolani and Vij play out. When Xolani tries to kiss Vij, he pushes him away, also when he tries to give him oral sex he pushes him away. In both moments Xolani is violently rejected. These are heartbreaking moments. They are moments that make obvious the intricate relationship between shame and desire, and the sometimes consequent violence. Xolani loves Vij, and I think Vij also loves Xolani, in his own way. But it is a love that cannot speak itself. It is a love that cannot be lived or expressed. It is a love that must quietly exist for a couple of weeks in a year, and even then, it must be hush about its existence. Xolani desires more than what Vij can give, and Vij is not willing to give more than he already has, which is not much to begin with. In this way, Inxeba borrows much from the queer archive of stories of love and double lives, of impossible arrangements where one is sustained for a year by a patchy intimacy of six weeks, and most of all the self-annihilation in the denial of one’s desires.

The irony about the circumcission tradition in Xhosa culture is that it is homoerotic. There are two examples I want to highlight of a homoerotic nature in the movie. Firstly, it is when the initiates are starting to heal, and they decide to show each other their penises. They play a version of “show me yours, I will show you mine” and it is hilarious. The queer initiate is excluded from this conversation. It is not uncommon for men in groups to play show-and-tell, and it is excused as “boys being boys.” The sexual tension that might accompany these show-and-tell moments is often underplayed or nullified. Secondly, when the boys are about to head home, when they are fully healed, the older men comment on the beauty of the circumcised penis. The talk of the penis as a beautiful organ in the movie is strikingly similar to the way my queer friends talk about penises when we are having “kitchen” talk.

Inxeba succeeds because of the richness of the characters of Xolani, Vij and Kwanda. It succeeds because it paints these characters as people with fluid and complex desires navigating rigid systems of identity and culture. These characters are real, they are people I know, I have seen them. This movie succeeds because it sidesteps the traps of portraying black characters on television and movies, particularly queer characters, as one dimensional. It challenges head on the overly simplistic notion that homosexuality is “unAfrican.” Homosexual desires exist wherever there are people. Our homosexual desires are formed in ways we sometimes cannot explain, but there they are. This movie opens up space where we can have a conversation about our desires, space where our desires matter. As a nation, we should all applaud John Trengrove and the team for an amazing job at story telling. Inxeba is an immense contribution to the queer archive in South Africa.