We should all be contributing towards making South Africa a better country for all who live in it. Our contribution towards the building a just and democratic society takes many forms, and this is why we can all play our part, no matter how small, to build a prosperous nation. I think the February 2018 issue of Cosmopolitan does its part in contributing towards a more open and more tolerant South Africa.

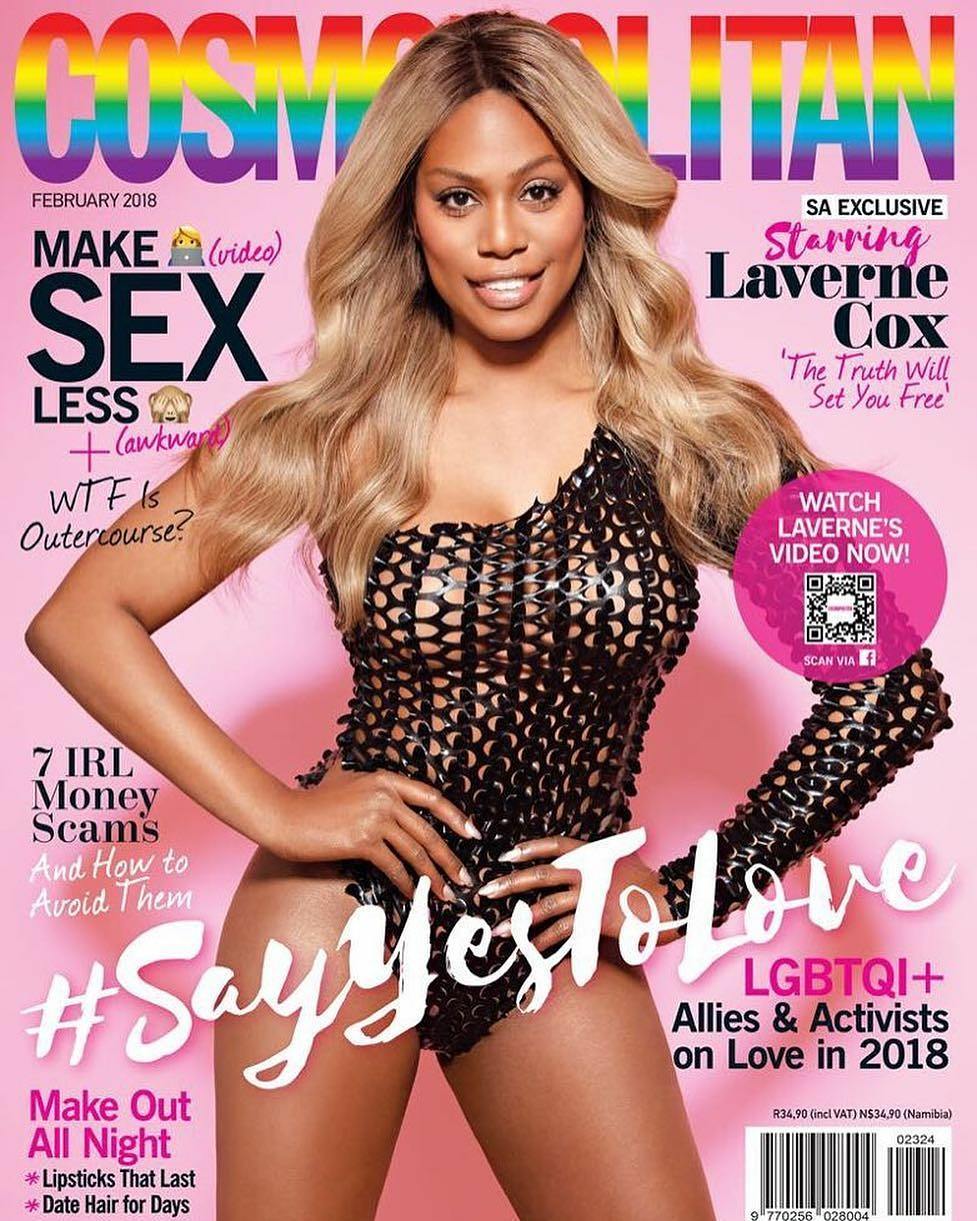

Although I am a magazine junkie, don’t usually buy Cosmopolitan magazine. I bought the February 2018 issue of Cosmopolitan because it has Laverne Cox on the cover. Laverne Cox is an actress, an Emmy-winning producer, and a transgender activist. Laverne Cox is the first transgender woman to be on the cover of Cosmopolitan magazine. She is the first because transgender women have been, and continue to be discriminated against in many societies around the world. Publications like Cosmopolitan have not regarded trans women as women. So her being the first does not mean transgender people have not existed before, they were largely ignored by beauty magazines.

In the interview, Laverne Cox speaks about her favourite things, her favourite people, and the new projects she is doing. Buy the magazine for the full lowdown. Two things stand out for me in the interview, that is her message to readers and the way she describes gender. She says to the readers:

“Let’s live a more fun, fearless life by embracing love for ourselves and each other and connecting to a purpose bigger than ourselves.”

When she describes gender she says:

“(Gender is) The spiritual experience of one’s gender as male, both or neither and simultaneously the social and cultural constraints that organise around a set of expectations. Cultural expectations and the individual, spiritual experience of our gender can be in conflict.”

Holly Meadows, the editor of Cosmopolitan South Africa, says that with this issue “we wanted to do our small part in providing a platform for visibility for the LGBTQI community.” I will assure you there is nothing “small” about this Cosmopolitan issue. It is big. Having Laverne Cox on the cover of this issue is a small part of a really amazing issue that celebrates sexual diversity while simultaneously providing some much needed education. All done in the beautiful “fun-fearless-female” language that Cosmopolitan is famous for.

The issue is packed with useful information about transgender rights, gender identity, and sexual identity. Early on in the magazine you read a discussion about coming out at work. One writer takes a pro coming stance while another rejects coming out at work and they share their reasons. Both sides of coming out are shared from a personal experience, and also what other people have gone through. The issue of coming out is relevant, and it will be relevant as long as people have to come out because society takes heterosexuality as the standard norm.

Coming out is something that was relevant in my research on same-sex marriage, because even though South Africa has same-sex marriage, people still struggle with coming out to family and friends. This tells us that LGBTI people continue to live under pressure to stay in the closet. What is revealed by same-sex marriage, or the process of marrying is that the coming out process is not a linear process, and it differs from person to person, and how marriage somehow facilitates a kind-of coming out process for some LGBTI people.

In the South African climate where LGBTI people are still in the peripheries representation continues to be important. So this issue of Cosmopolitan recognises that and throughout the issue some of South Africa’s LGBTI icons, artists, celebrities, activists, and sports stars are featured. It showcases the important work done by activists, but also the contribution of artists and other celebrities to South African cultural life. The magazine highlights some of the contributions by LGBTI South Africans to the nation.

In the issue there is a “The Rainbow List” which really chronicles the historic LGBTI moments in South Africa post 1990. With all the negative headlines mostly about violence towards LGBTI people in the newspapers, it can be easy to forget the amazing gains made in post-apartheid era. The magazine provides a little LGBTI history and some of the historic television moments, including that controversial same-sex kiss between Thiza and Thabang in Yizo Yizo. I remember the conversation that kiss caused and how excited I was to witness the scene. This Cosmopolitan issue takes you down LGBTI memory lane in an easy and accessible way. Of course, the little history depicted in the issue is not exhaustive, but some of the moments that were important, moments that caused all the conversation and had an impact on the South African consciousness.

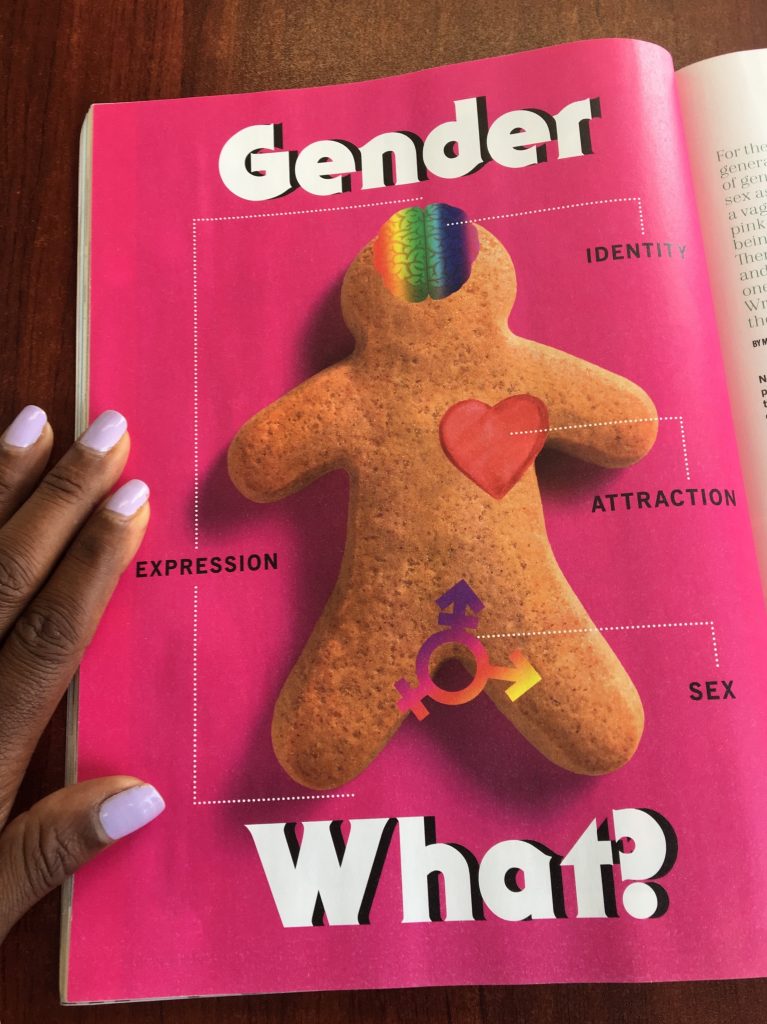

I really appreciate the “Gender What” section, where a number of people talk about their gender identity and their gender performance, and generally how they see themselves and their sexuality. The people featured in this section speak candidly about the limited societal conceptions of gender and how there’s so much more to people than “male” and “female.”

Of course, this is a magazine; so all of this amazing gender and sexuality talk exists amongst advertisements of perfume, lip gloss, and all kinds of fashion items.

The section that focuses on different people with their different genders and sexual orientations is very powerful. It showcases people from all walks of life who note some of the ways they experience life in their non-normative genders and sexuality, and most importantly they all describe what love means for them. They give us quotable quotes about love, and what emerges from this spread is that love is important to all of us. The spread is a rainbow of people with different takes on love. People from all walk of life with different sexualities and genders but connected by a desire for love and wanting to share love.

This is a wonderful issue from a mainstream magazine like Cosmopolitan. It gives one hope about a different world where the porousness of gender and sexuality will be common knowledge and celebrated. Where an issue of Cosmopolitan with a transgender woman on the cover will not necessitate a write up like this one. Well done to Holly Meadows and the Cosmopolitan team for a fun and fearless issue that really demonstrates that not only do #TransLivesMatter but that #TransIsBeautiful and that we can #SayYesToLove in all its different varieties.