Last year, I spent Easter Weekend in Hamburg, Germany at an Easter Brunch hosted by a good friend of mine. This year, I spent Easter Weekend in a small village, Goshen, in the Eastern Cape. The village is nestled in one of the many valleys in the Amathole Mountains. The nearest “town” to the village is Cathcart. What brought me to Goshen was the Makwande Republic Experience. It was described as a “creative meander” that was organised by the formidable Ukhona Mlandu. This was my first time in this part of the Eastern Cape. It’s interesting that I had never been to that part of the country considering that I grew up about 300 kilometers away from Goshen, I grew up in Port Elizabeth. Of course, part of the reason that I never went to Goshen is exactly because I grew up in Port Elizabeth (PE). The biggest “city” in the Eastern Cape, in other words, people in other parts of the Eastern Cape come to PE, not the other way around. I have since seen the limits of such thinking. My experience in Goshen has further demonstrated the shortsightedness of such mentality, as there’s so much to see and experience in many other parts of the Eastern Cape.

When I received the invite to the Makwande Republic Experience, I knew immediately that I wanted to attend the Art Meander. After deliberating on the best way to get there, I settled on a ten-hour road trip from Cape Town to Goshen with two good friends and the cutest-brood-inducing toddler. The road trip was fantastic. It was filled with all the things that make a road trip, stops in cute small towns for coffee breaks, conversations about everything under the sun, the state of South Africa, and our soundtrack was Angry-Girl-Music. But the drive between Fort Beaufort and Cathcart was the absolute best in terms of scenery. I could not get enough of the mountains “waar die kranse antwoord gee”, the winding roads, the never-ending valleys, and the lushness. It was so green, and of course, everything seemed that much greener than usual because in Cape Town there is a draught.

When we arrived in Goshen, it was around 19:00 the village was quiet. It was expansive. The sun was going down but it was still light out. It was serene. It was beautiful. The homesteads were far apart. Goats were roaming. Many of the homesteads had quintessential Xhosa village housing like rondavels, while some were built in “modern” suburban housing structures. While taking in the scenery of the village I realised that as someone who grew up in a township, seeing and experiencing village life is exciting and also an education in South African land politics. The ways that townships were created, and continue to be created is radically different from the layout of the villages. While taking in my surroundings, I wondered to myself how my life would have turned out if I had grown up in a village like this one.

As I was meeting others who were also here for the Makwande Republic Experience, there was a bonfire starting, and people were huddling around the fire. While in Goshen all of us “city” folk visiting the village stayed in different homesteads all over the village. I lived with an incredible woman, who was born in Goshen, but spent most of her life in Johannesburg. We had the most amazing conversations about life in the village; her work life as a nurse in Johannesburg, and about how difficult life was for her when she first moved to Johannesburg because of apartheid. We had such a great rapport, that she gave me as a gift this beautiful hand made bag. The bag really belongs in a museum more than it belongs in my closet. I am convinced that she sensed that I was queer and that I love beautiful things, hence she gave me the bag. The kind of homophobia I experience in Cape Town was absent in Goshen, even though I was clearly Ouma-se-kind. The kind of welcome I felt in Goshen is the kind that I used to read about in Xhosa books like Unojayiti Wam.

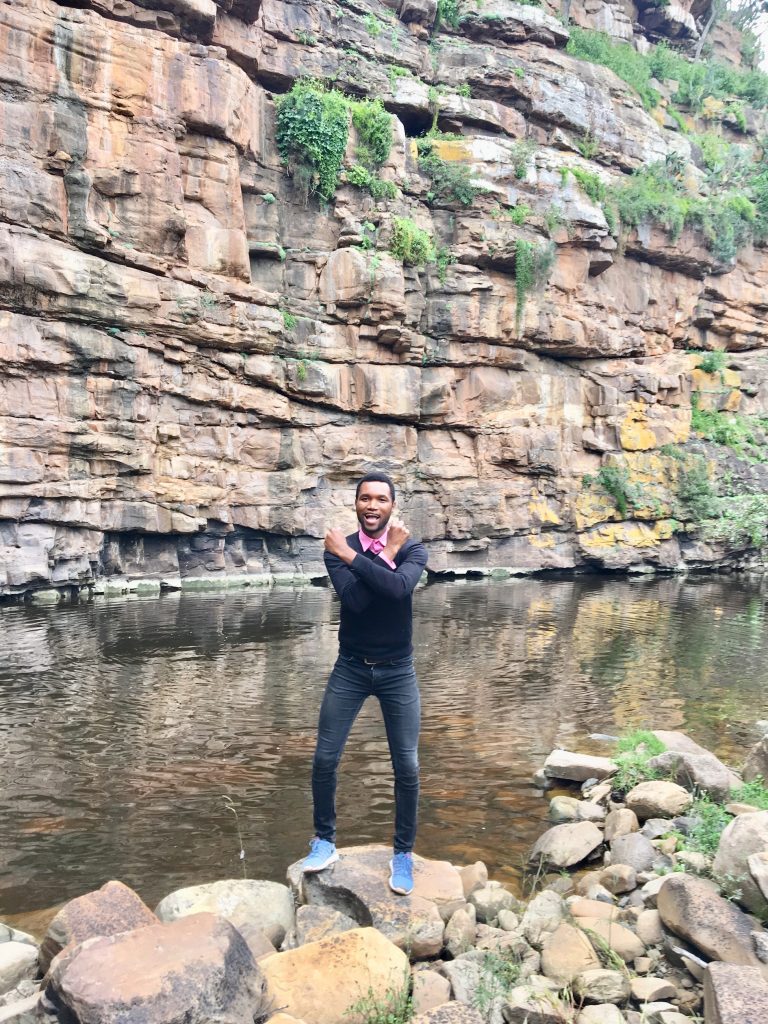

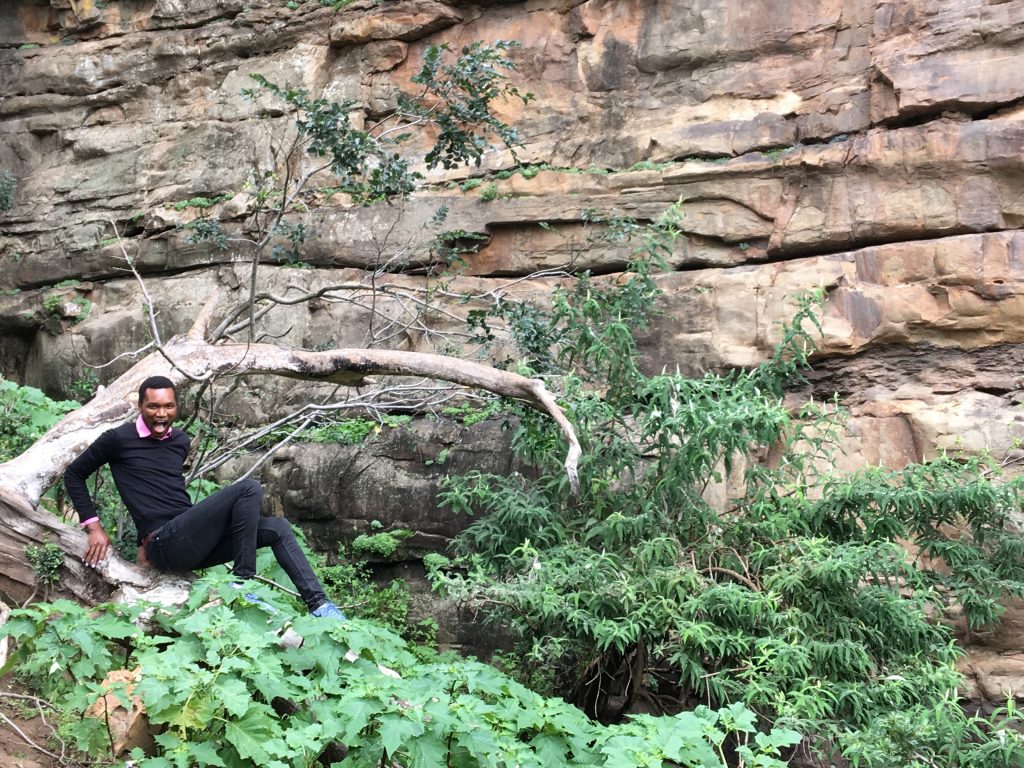

One of the most beautiful experiences in Goshen was the hike to Iliwa lika Mqede (Mqede’s Valley). The valley is not visible when you are in the village, but the whole village faces the direction of the valley. The hike was incredible. We walked across what used to be farming land but was now used for grazing by cows and goats. We also walked past a beautiful area called Entilini, where I envisioned a beautiful Cape Dutch style house for myself surrounded by rondavels. When we arrived at Iliwa lika Mqede we couldn’t shut up about how eerily it looked like the background of the fighting scene in Black Panther before the coronation of the king. From then on throughout the weekend we would make connections between Makwande and Black Panther’s Wakanda. After relaxing and taking lots of pictures, we hiked back to the village. When we arrived back we were tired but fulfilled.

After the big hike, we arrived at the village with firewood from the fields for a bonfire. After a bit of rest, we were summoned to a homestead nearby to participate in a traditional ceremony. The ceremony was a thanksgiving to the elders. When we arrived at the rondavel of the homestead, we were asked to sing as we enter, as it is traditionally done in many Xhosa festivities. You announce your arrival with a song. The Xhosa way of knocking is a song. So of course, we sang, Nilelena? Nilelena?, Nanku umntu enqonqoza, Nanku umntu esiza. The music created a jovial atmosphere where we danced and sang with the village people before we had even shaken hands. This was a special moment; here we were at the home of people we had never met, we were asked to sing as a way of first encounter. No shyness. No embarrassment, just greetings in song. We sang on top of our voices, we clapped our hands; the village people inside the rondavel joined us. I was touched. I was flying. And the acoustics inside the rondavel were fantastic.

We were offered food and a drink. We were also offered sorghum beer. We drank from the communal bhekile. The elders from the village conversed with us. There was one man who welcomed us. He spoke beautifully about how we were now part of the village, and how we are welcomed to come back. He spoke about how our spirits will stay in Goshen, and we will also take with us Goshen spirits. It was a beautiful connection with elders and young people while drinking sorghum beer and praising the ancestors.

Later on, more visitors arrived, and more singing ensued. When the second round of singing began, the Xhosa drum came out and one of the women from the village began playing the Xhosa drum. The drum was made of cowhide. The cowhide was white and brown. It was a beautiful drum; it looked new, as there were no signs of wear and tear just yet. I love Xhosa drums. I have one myself, and I often play it when I need to hear that unmistakable Xhosa sound. The drum playing skills of the woman who played the drum were incredible. She could go up and down, soft and hard, middle of the drum and outer parts of the drum, all of which create different sounds. Her playing summoned the ancestors. I was so taken by her and her skill that I almost asked for lessons. I think next year when we go to Goshen, they must introduce Xhosa drum lessons.

After the second round of singing started, we never stopped. We were all sick with song in that rondavel. Besixhentsa. Sicula. Siyiyizela. With the sound of the drum, the Xhosa melodies, the moving of our bodies, all inside the rondavel, I was transported to another universe. There was something magical about that space, something otherworldly, something that was out-of-body-experience about being in that rondavel with my people. In many ways, it was healing to be there, in that I never had to explain myself. There was a way in which I was accepted, even though I was a foreigner in that I am a city mouse invading the country, I was welcomed with love and without suspicion. The village people were sharing with me whatever they had, and I was touched and felt honoured.

Since I left Goshen I have been listening to Amanda Black’s Amazulu. She captures my experience at the Makwande Republic Experience in Goshen in the Eastern Cape succinctly. My experience at the Makwande Republic is particularly captured when Amanda sings:

Drifting

I’m drifting away

Into the darkness

Ndizothath’ umthwalo

Ndimbeke emqolo mama

Ubomi bunzima

So lift my head up high

Open my eyes

And I will fly oh

I’m barely coping

I’m feeling closed in

Looking up, hoping

The heavens will open

Mdali wezulu

Ndikhalela kuwe

Open up, open up

I’m feeling closer now

The light is shining brighter but I’m losing my flow …

Avuleka avuleka avuleka

‘Vuleka amazulu

‘Vuleka amazulu

‘Vuleka amazulu

Avulekile Amazulu indeed.

This was the inaugural Makwande Republic Experience. Personally, I am excited about the next Makwande Republic Experience. This was the beginning of something special. It was a meeting of the minds kind-of place. It was a place where blackness can be without having to explain itself. It was a place where Xhosaness is celebrated, not as an appendage to something else, or as “heritage day” but as an ordinary way of everyday life. I have been inspired by what I experienced at the Makwande Republic and I am excited to have a creative giving back to the village when I attend the next Makwande Republic Experience.

What Ukhona has done with the first Makwande Republic Experience is inspiring. Makwande Republic is an idea that was materialised. Ukhona demonstrates to us as young black South Africans that we must use what we have where we are to create the futures that we think we deserve. With the Makwande Republic, Ukhona embodies the words of June Jordan that “We are the ones we have been waiting.” May we learn from this amazing creative meander, and may we replicate it in our own ways where we are. Makwande indeed! Kube chosi Kube hele.

Some of the photographs were taken by Ukhona and others by Laura.

Some of the photographs were taken by Ukhona and others by Laura.