My adoration of Grace Jones started when I travelled to San Francisco for the first time. I was doing my Master’s in Minnesota when I visited San Francisco during San Francisco Pride. It was real a pilgrimage. I was wide eyed and intrigued. I had heard and read so much about the city by the bay and I was intrigued and mystified and absolutely thirsty for this gay mecca that everybody seemed to rave about. My imagination was obviously too limited to really imagine San Francisco, it was gayer, more beautiful, and so forbearing, than I could have possibly imagined. I had died and gone gay heaven.

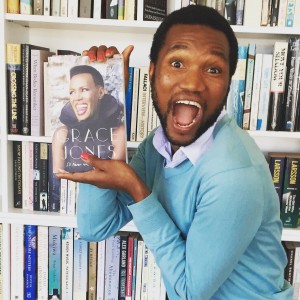

When I was in San Francisco I met Kevin, who would become my guide to the city, my reason to go back to the city, and a very dear friend. When we met, one of the first things he said to me was how I reminded him of Grace Jones. He was the first of many people who shared this sentiment during San Francisco Pride that year. To put things in perspective, the Grace Jones references were fuelled by the hairstyle I had at the time. I had a flat top hair cut with red cornrows on the side, about three on each side of my head. This created a striking, almost square shaped face that was feminine yet still masculine. It created this androgynous look. I was born in the mid 80’s, so I was born when Miss Jones was at the pick of her modelling-acting-singing-performance artist career. And when I came of age she had decided to stop recording because of her dissatisfaction with music industry. So of course I would only make the connections, and realise the enormity of the compliment from Kevin much later when I started to learn more about Grace Jones and started to appreciate her art, her life philosophy, and just about everything about her. I was in my early twenties when I started listening to her records, and this was decades after her last recorded album.

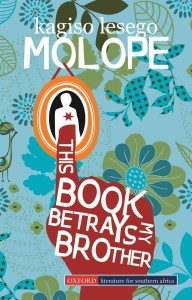

Since then, I have followed Miss Jones and she has been more than just inspirational. She has been my guide to living a life according to my own rules, and not bowing down to the societal pressure to be normal and therefore average. Grace Jones’ memoir, I’ll never write my memoirs, is probably the best memoir I have ever read. Granted, I don’t read many memoirs; it’s not a genre I am particularly fond of. But Miss Jones’ memoir is not just any memoir; it’s a chronicle of a life lived without boundaries, dangerously on edge, and completely at odds with the mundane, the slow moving, and the expected. One of the stories that captured me is within the first 100 pages of the book is when Miss Jones describes her first orgasm. She writes:

“Shaving my head led directly to my first orgasm. This is because I am fairly sure the man I had my first orgasm with was Andre, my hairdresser from Cinandre… These days they say DJ’s are god. Back then it was hairdressers who were God… He definitely knew what to do with me. My hair could be adjusted, changed, edited, in much the same way that later my whole body would be treated. He was the first one to style my hair short… I suppose it’s not surprising that my first orgasm was with Andre. His fingers on my scalp working their magic helped… I’d never had sex like that before. It was sex from another era, another solar system. It still started with the mouth but it ended up beyond the body. It made me feel like I was falling backward in time. He was very open-minded and creative, and that seemed to spill over into the sex. He bent me out of shape.”

To say that Grace Jones is sex positive would be an understatement. She celebrates her sexuality; she celebrates her body and takes her sexual pleasure seriously. The description of her first orgasm is poetic, all consuming, and infused with process of beautifying – her hair being cut. Her life is so art infused that even her first orgasm is artful. In the memoir she transports you to that moment, and for a minute I was searching my memory for my first euphoric sexual moment, and it failed to compare to the one Grace Jones had.

There is a refreshing honesty in the memoir. She doesn’t seem to hold back; even her mistakes and misfortunes are laid bare for the world to see. I suppose that’s the power of living your life with integrity, and being honest to yourself about who you are and what makes you who you are. She writes about her sexual encounters, the relationships, the breakup; the reasons for breakups, and of course the drugs. The laissez faire attitude towards narcotics is enlightening. Often when celebrities open up about their use of drugs it is filled with regret, and is linked to moral failure and repentance. Grace Jones’ approach to drugs seems to be ‘use but do not abuse.’ The legendary parties she used to throw had Grace Jones dubbed “the Errol Flynn of the 80’s” and these parties have now taken a mythical narrative. She says “at my parties, I would let people do what they want as long as the didn’t die. That was the number one rule. People could have all the fun they want, but no one should die. No overdoses, no drinking in the bathtub. No accidents. Don’t spoil the party. If you wanted to kill yourself you had to leave the house and walk across the highway.” The directive is very clear, and this is probably why to this day we have never heard of a drug overdose from any of her parties.

When miss Jones started out as a model, she struggled to establish her self in New York. Her “look” was rather too much for the American sensibility. She was dark skinned, boyish skinny, androgynous, and in no way representing classic or ordinary ready-for-vogue-beauty. So following in the footsteps of Josephine Baker, Nina Simone, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and many other African Americans, Grace Jones moved to Paris for a better chance at a modelling career. Indeed her modelling career took off in Paris with artistic magazine covers and photo spreads. It would seem the French and Europeans at large were much more excited about her “look” than the Americans. Although she didn’t speak French when she arrived, she had Latin roots through Spanish and she learned “French in three months flat.” Her attachment to Paris would last throughout her life. The Paris years were dreamy, although she was hustling, they are so mystical and glamorous and read like a movie script. It is also during this time that Grace Jones meets her lifelong friends Jerry Hall and Jessica Lange. I particularly loved reading about her life in Paris because I love Paris and all things French. It is a love that has been fuelled mostly by novels by African Americans who have moved there post World War Two. Grace Jones makes me want to live in Paris.

My obsession with Grace Jones has to do with my love for art and artistic individuals, because I see artists as almost supernatural beings. I am not an artist; at least I don’t see myself as one. Although one of friends once said that the way I put myself together could be considered art. The way she describes the creative process of how she came up with some of her songs with her collaborators is a marvel. There is something intriguing about learning about the genesis of songs like La Vie En Rose, My Jamaican Guy, and Slave to The Rhythm. There is no doubt about the commitment Grace Jones has to her art. She is heavily involved in all of her productions; she wants to have creative input if not full control of her art. She rejects being just a muse. She attracts artist who are interested in creating something new, something different, and something that has not been done before. She celebrates what makes her different, she lets others mine what makes her different and create something artistic out of it. She knows that she is not a conventional beauty, which is why she had to go to Paris to pursue modelling, but instead of hating her difference, she uses her unconventionality for artistic expression.

Her unconventional beauty is matched by her unconventional approach to being a star or a celebrity. She goes as far as to say “I am not a Diva. I am a Jones.” She rejects fame for fame’s sake. She rejects being part of the pack, or a being grouped with other female entertainers. When she was coming up, and starting to make records, producers wanted her to sing like the superstars of the day, people like Aretha Franklin and Diana Ross and she rejected these proposals. The aim is not to be like someone else, the aim is to be artistically interesting, to create something original that has the potential to outlive the artist. The most quoted sections of the book by reviewers are the sections towards the end of the book where she talks about young stars, and what is lacking in female entertainers today. It’s very provocative how she names entertainers who she thinks have copied her. But all of this is done to demonstrate just how different she is, and how far ahead of her time she was. Her artistic philosophy is summed up when she writes:

“I come from the underground. I am never comfortable in the middle of the stream, flowing in the same direction as everyone else. I think people assume that’s where I want to be, famous for being famous, because as part of what I do there is a high level of showing off, but my instinct is always to resist the pull of the obvious. It’s not easy, especially when you have had any sort of success, because the people want you to repeat what it was that made you a success, even if your instinct is to move on, or to want to change, or have other ideas.”

Her disdain of being compared to or told to sing like other female entertainers by record companies is but one example of her living feminism. When you are Grace Jones and you have lived your whole life according to your own rules and have singlehandedly defied and redefined beauty standards of the modelling industry and used your body for sexual pleasure and to create art that challenges norms, you don’t need to go around saying you are a feminist. When you are Grace Jones your whole being and everything you touch is feminism and challenges patriarchy. The feminist thread is weaved throughout the book. The book is a feminist force of how to live a life that undermines patriarchy. When she signed a lucrative recording deal with a Capitol Records, they tried to interfere with her creative vision and she lashed out. She writes: “I was female, and they decided that I was rock and roll insane. Had I been a man, they would have considered I was retaining control, or professionally fretting about the details… You can tell why there are so few female film directors. It’s the same with any job that society has decided can only be done by a man: They find ways to undermine and undervalue a woman doing that job. And the fact that you end up saying ‘they’ makes you sound paranoid… What are the chances of a female president being elected? The men-only corporate reaction is: what about the tampons? Will she bleed everywhere? What if she gets pregnant? What if she is going through menopause? … It’s the same old caveman shit, a power thing. It’s why I want to fuck every man in the ass at least once. Every guy needs to be penetrated at least once. Do it yourself if you want. But that’s the vision – a woman lies there and the man goes in, takes control, whoosh. It’s all about power. The woman is always in the vulnerable position, and the man takes control. Come on. Everybody can be penetrated – mentally too. Slowly, slowly, it changes. Too slowly.” Grace Jones raged against the male corporate machine that wanted to exclude her from the creative process of her own music, and market her like any other female artist. This is what sets Miss Jones apart from her contemporaries and younger artists; she refused to be neatly packaged for commercial success.

Just like Grace Jones doesn’t go around talking about how she is a feminist, because it is painfully obvious, she doesn’t go around chest thumping that she is a gay icon. Grace Jones’ status as a gay icon is like everything else about her, underground. Her first encounter with a gay man is her brother, Chris, who she was very close to growing up. Grace Jones used to go with Chris to gay bars, so she was exposed to gay people and gay culture early in her life. Although Grace Jones has collaborated with gay artists, is close like twins with her gay brother, she was close friends with renowned gay artists like Andy Warhol, she performed in underground gay bars in New York in the late 70’s and early 80’s, she has never branded herself a gay icon. Her memoir is filled with stories about gay men she worked with and some she had crushes on when she didn’t know they were gay. And all of this is treated as but one of the many threads in Grace Jones’ life. And this for me makes her more of a gay icon than the chest thumping icons.

There’s a point where Grace Jones reflects on her friends who died too young in the 1980’s and early 1990’s due to HIV/Aids. It’s a sobering read because she had so many gay men in her life, so she experienced many deaths and the paranoia that followed. It was Tina Chow’s death that really shocked Jones. “Tina’s death made it seem closer than ever. You couldn’t help but think of the people you had slept with or, even more so, of the people who had slept with the people you had slept with. It had been easy to sleep around. In the places I was, everyone was so sexual. In Paris, it was food and sex. Wine, food, and sex. You can’t leave out the wine. Sex was a vital point of individual freedom. It was meant to lead to more life, not death.”

There is no disputing the queerness of Grace Jones. If queer is understood in the David Halperin sense where queerness is about the transformational power of the queer identity. Halperin speaks of a transformative potential of queer culture that Foucault also emphasised. According to Halperin queer is an identity without an essence, not a given condition but a horizon of possibility, an opportunity for self-transformation, a queer potential. This queer conception of identity aims to demolish boundaries; it sets no limits to the ways in which queers can potentially organize their lives. Halperin might as well have described Grace Jones. Grace Jones embodies the essence of queerness. She disrupts the norm; she challenges conventions of beauty, of womanhood, and sobriety. She is someone I look up to for inspiration for a life lived according to one’s own rules. It takes courage to reject the mainstream and to create one’s own path. It requires courage of conviction and a knowing of the self to live your truth without apologies. What a life Miss Jones.

Lwando Scott