Today, 30 years ago, the first Lesbian and Gay Pride March in South Africa was held in Johannesburg. The Pride March was organised by the Gays and Lesbians of the Witwatersrand, led by Beverly Ditsie and Simon Nkoli. When the Pride March took place, I was knee high to a grasshopper and had no idea what was taking place in the country politically. The seeds that were being sown at that Pride March would affect the trajectory of my life as a young queer kid growing up in South Africa.

Growing up I remember seeing the Johannesburg Pride March on the SABC news and hearing people around me passing all kinds of remarks about gay people. So, while I was interested in the Pride March and what I was seeing on television, I did not make my interest known. As a queer kid in Kwazakhele I wasn’t sure what Pride was, all I saw were people wearing interesting clothes with placards who were involved in something that looked like a “Toyi Toyi” and a Toyi Toyi was something I was already familiar with. Toyi Toyi had been a mainstay of South African society and therefore the news, so that element of the Pride March I could figure out immediately.

As I grew older, and grew into my queerness, I started to seek queer media like Gay Pages, EXIT, and other international gay magazines, and through these reading materials I would learn more about Pride.

I only really understood the history of Pride when I went on a study abroad trip to the United States in my second year of university. It was here that I was exposed to the history of the Stonewall Riots of 1969 that took place in New York City. The realisation that there were so many queer people in the world was profound. Learning about this history had a great impact on me because growing up, I had only thought there was me and a few others who were queer. Existing in isolation. Queer people were not part of the curriculum in school, and even at university, there were no classes that touched on queer people or the sexuality movement’s history. So, in many ways, my study abroad trip helped to shape the way I saw my queerness and helped me situate the Pride Marches I had been seeing on SABC news over the years.

I attended my first pride in 2007 in Cape Town. I was in my first year of postgraduate studies, in other words, I was in my honour’s year at the University of Cape Town. Cape Town Pride takes place early in the year, February, and so I was just fresh from Port Elizabeth when I attended Cape Town Pride. I had met a group of Swedish visitors in Port Elizabeth just before I left PE. I had served them at the restaurant I was working at in Port Elizabeth, and coincidentally they were going to Cape Town after their time in PE and we exchanged numbers. I met up with the strange group of Swedish young people who were friendly and sweet. The young Swedes made my first Pride memorable as we went marching through the streets of Cape Town.

I remember that I wore the tiniest shorts and a small pink t-shirt on that day. It was also during this time that I was obsessed with Ntlantla Nciza of Mafikizolo fame’s bug-eye-sunglasses that covered half your face from their Sophia-Town-inspired music and dress during the 2000’s. I remember feeling on top of the world during Pride, and marvelling at such a glorious gathering of queer people from all works of life.

The Pride March started in Somerset Road in Green Point and went through the CBD, moved through Adderley Street, and up Wale Street, and then went back to Green Point via Buitengracht Street where there was a huge party. To think this was 12 years ago, and so much has happened to Pride politics in South Africa since then. I suppose in many ways, the political contestation preceded my attendance of Pride but have, indeed, intensified in the last couple of years as we all struggle with the meaning and politics of Pride in South Africa.

Since my first Pride in 2007, I have since attended Pride events in other parts of the world. I have seen the different ways that other countries and cities organise Pride and some of the politics involved in organising Pride. I remember being awed by the magnitude and glory that is San Francisco Pride. I had never been to a “world city” Pride like San Francisco before, where the size of the Pride itself was hard to wrap your head around, and you must accept that you will miss most of the Pride because it’s impossible to see everything.

I have attended Minneapolis Pride with friends I met while studying in Minnesota. This was a radically different experience from San Francisco, both in magnitude and also in the way in which people approached Pride. Minneapolis Pride was midwestern in nature, like a “mom and pop” shop, while San Francisco was like a “corporation” (Thanks Mariah). While on holiday in Nice, France, my boyfriend and I discovered that our visit coincided with Pride, and so we participated in the Pride March and the party afterwards. The Pride March was relaxed, and the after party was also very laid back, held at the pebble filled beachfront in Nice. These experiences demonstrated to me that different places do Pride differently. Although the premise of LGBTI rights and the fight for equality is reflected in most Pride Marches, many places go about it in different ways.

On this 30th anniversary of Johannesburg Pride, I thought it was important to reflect on Pride in South Africa since it has been mired in controversy over the past couple of years, and some would argue, it has been controversial since the 1990’s. It is also important to reflect on Johannesburg Pride because when it took place 30 years ago, it was an important moment for LGBTI rights in South Africa.

When I attended Pride in Johannesburg in 2012, the Pride March was disrupted by a group of black feminist lesbians from One-In-Nine. I was moved by the One-In-Nine disruption of Johannesburg Pride and their calls for a minute of silence for the lost lives of black queer people, particularly gender non-conforming black women. One-In-Nine also demanded the reinsertion of politics into Pride and the decommercialization of Pride. The response from the Johannesburg Pride organisers that year was hostility, walking and talking over the protesters, and even racists remarks that the One-In-Nine protesters should go to their “lokshins.” This was a painful moment in the history of Johannesburg Pride. It was a moment to pause and reflect on LGBTI politics in South Africa.

In trying to make sense of this moment and what it meant for Johannesburg Pride, but also for LGBTI politics in South Africa, I wrote about this disruption moment. The piece was published in the journal Agenda, titled, Disrupting Johannesburg Pride: Gender, Race, and Class in the LGBTI movement in South Africa. This was my attempt to use intersectionality to argue for a more nuanced understanding of LGBTI politics in South Africa. In the piece I conclude that in South Africa we need to decolonise the LGBTI movement where the movement takes seriously the postcolonial issues that South Africa suffers from. Also, I argue, there is a need for postcolonial thinkers, and people in the postcolony to seriously engage LGBTI politics as they manifest in the postcolony. I argue that this will enable us to engage and imagine a better future for LGBTI people in the postcolony.

With the stratification of South African society, the politics of pride is complicated. This is demonstrated by the different Prides that have been created outside of the main Pride events. It is really in response to the hostility found in the “mainstream” Pride in the major cities of South Africa, that alternative Pride events have been established. One such Pride event is Khumbulani Pride which takes place in different townships around Cape Town around April.

Khumbulani Pride has become an important annual event that centres the lives of black LGBTI people in their backyards. It is a Pride March that also helps to conscientize the communities in township spaces about LGBTI lives. Khumbulani Pride engages in a particular politics with black communities ensuring that LGBTI people are seen. An example of this is how during Pride state service providers like the South African Police Services are engaged with in order to establish and nourish relationships that would help end hate crimes.

The physical and sexual assaults on LGBTI people, particularly those who are gender nonconforming is an ongoing violation, and the communities where these violations take place need to be engaged with if we are to end the violence. This is what the black feminist lesbians from One-In-Nine were trying to articulate with the disruption of Johannesburg Pride. That the lives of black LGBTI people matter and that there has to be space and a place for politics in Pride. The One-In-Nine members were demanding rights for ALL LGBTI people, and not just those who are white, who are middle class, male, or those who are cisgender.

In South Africa there is often a tendency to ignore or bypass complexity and nuance. Ironically, this is exactly what is necessary to understand the post-apartheid moment as South Africa democratises. We need to me more nuanced and be able to learn to hold two, or more, seemingly contradictory truths at once. South Africa is an incredibly diverse place with different ways of life, and this demands that we are empathetic to others who do not live, and love like us.

I was very excited when I saw the promotional artwork for Johannesburg Pride 2019. The promotional material includes a colourful image with the inscription “Pride of Africa” which is befitting for the celebration of 30 years of Pride in Johannesburg, and by extension in South Africa. Johannesburg, and Cape Town Pride for that matter, have been heavily accused of non-inclusivity and focusing on the needs of white middle class men in the choice of venues for pride events, and the route that the Pride March takes. It has seemed, for the most part, these complaints have fell on deaf ears. What this year’s Johannesburg Pride has in store is to be seen at the end of October. What I have gathered online, there’s been some complaints about the programming not prioritising queer artists. It is my hope that Johannesburg Pride organisers rectifying the non-inclusiveness of the past Prides. I hope they take seriously the calls to be more inclusive.

Pride has played an important role in shaping my queer identity. Whether it is through reading about Pride, looking at pictures of Pride from different places in the world, or me physically attending Pride, Pride creates a sense of connectedness to other queer people. It provides us with a sense of safety in numbers, but also a sense of safety in being yourself in amongst people who “get” you. The question of safety, both emotionally and physically, can’t be taken for granted in the atmosphere of endemic violence in South Africa.

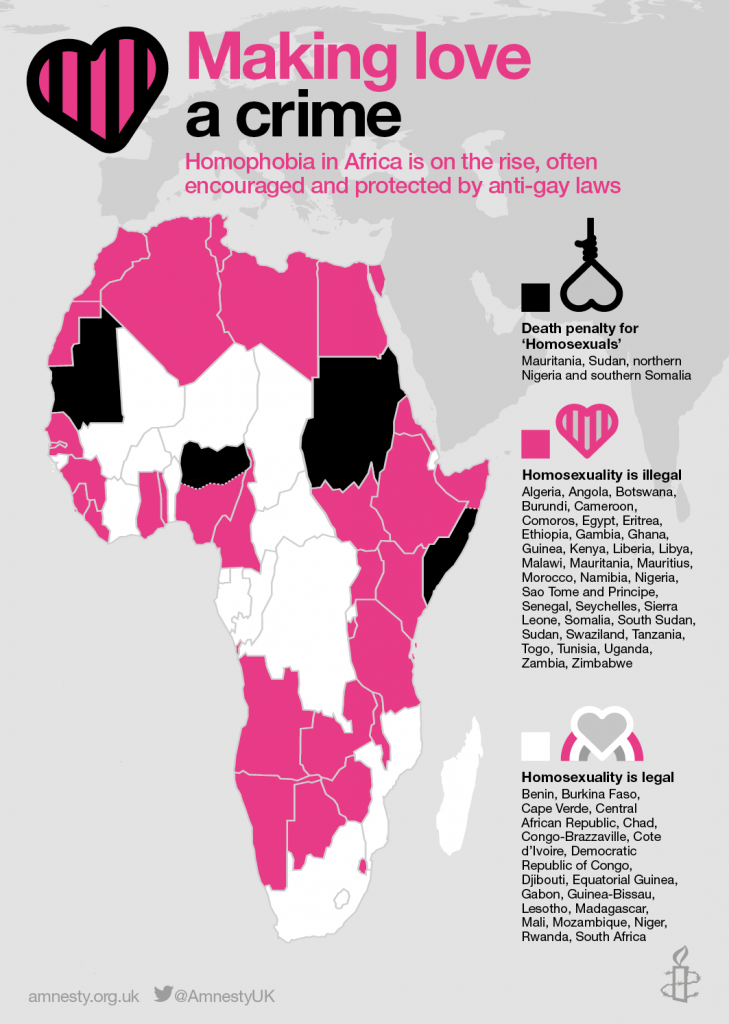

It is my hope that as we celebrate 30 years of Johannesburg Pride, we think about what pride means to us. To think about what we want Pride to look like. It is my hope that we pursue a Pride that is imbued with politics, that understands that in its essence Pride is Political. I hope that as we celebrate 30 years of Pride, we realise that LGBTI includes more than just gay and lesbian people, that we take seriously bisexuality politics, the issues faced by transgender people, and we seriously engage intersex issues, particularly as it pertains to children. It is my hope that we will recognise how our queer struggles are intricately linked to the struggles of the poor, to the struggles of farm workers, and the struggles of mineworkers. It is important for us to make the connections between queer struggles and the decriminalisation of sex work in South Africa. It is my hope that we see the links between forces of Afrophobia (that is often called xenophobia) in South Africa and queer struggles.

All of the struggles I mention above have one thing in common, it is people who are othered, they are seen as not belonging, they are seen as outcasts, they are poorly treated by the state. Sounds familiar? That’s because it is familiar, it is how we as queer people have long been treated by the state and society at large. It will do us good – and the South Africa we want to live in of the future, a South Africa of tolerance, freedom, where people experience love, and have dignity – for us not to forget that we as queer people, not so long ago (and continue to do so), were once othered, harshly. It is through this remembering that we are able to empathise with others who might be less powerful than us at this juncture of human history.

As we move forward, may we continue to strive for relationalities that surpass the limits placed on us by Eurocentric, patriarchy-obsessed, capitalist, and religious normativities, and the socially constructed fear of difference.

I want to wish all queer South Africans a happy 30th celebration of Johannesburg Pride. May we move forward with the yearning of a queer utopia where love, dignity, and freedom are in abundance. I hope this year’s celebrations of Pride bring us together like Simon Nkoli and Beverly Ditsie had envisioned in 1990, so that wherever Simon Nkoli might be, he can rest easy and chuckle to himself saying, “even with brown bags on our faces, we did a good thing.”