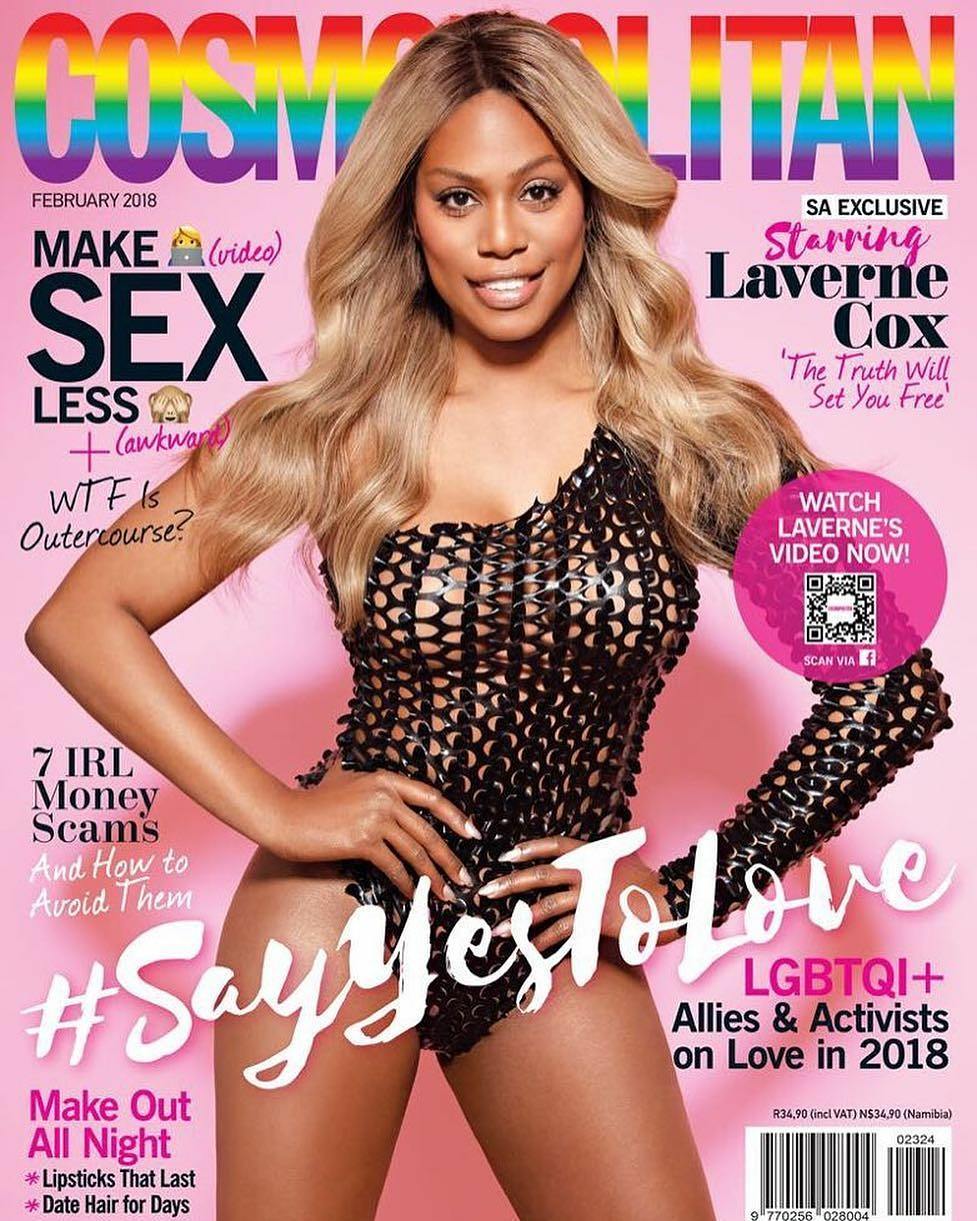

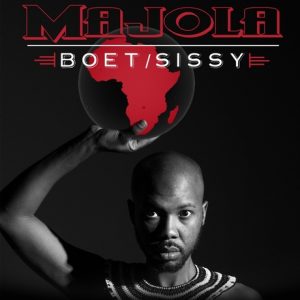

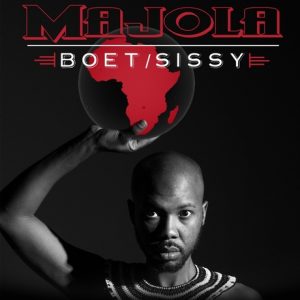

I was introduced to Majola’s album, Boet/Sissy by a friend who tagged me on Facebook. I immediately went online to have a quick listen, and then bought the album instantly. The subject matter of the album is of particular interest to me. The album focuses on the experiences of a black gay man, trying to make sense of the world. The album is the life journey of a black gay man predominantly sung in Xhosa. I love this album and I am with Majola in the politics of this album. This album is the epitome of being young, gifted, queer, and black. In this piece I embrace and celebrate Majola’s work talking to all the ways that this album resonates and inspires me. Boet/Sissy is a poignant reminder of the artistic talent in South Africa, but also of the myriad of stories we are yet to tell about what it means to live with the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality, in post-apartheid South Africa.

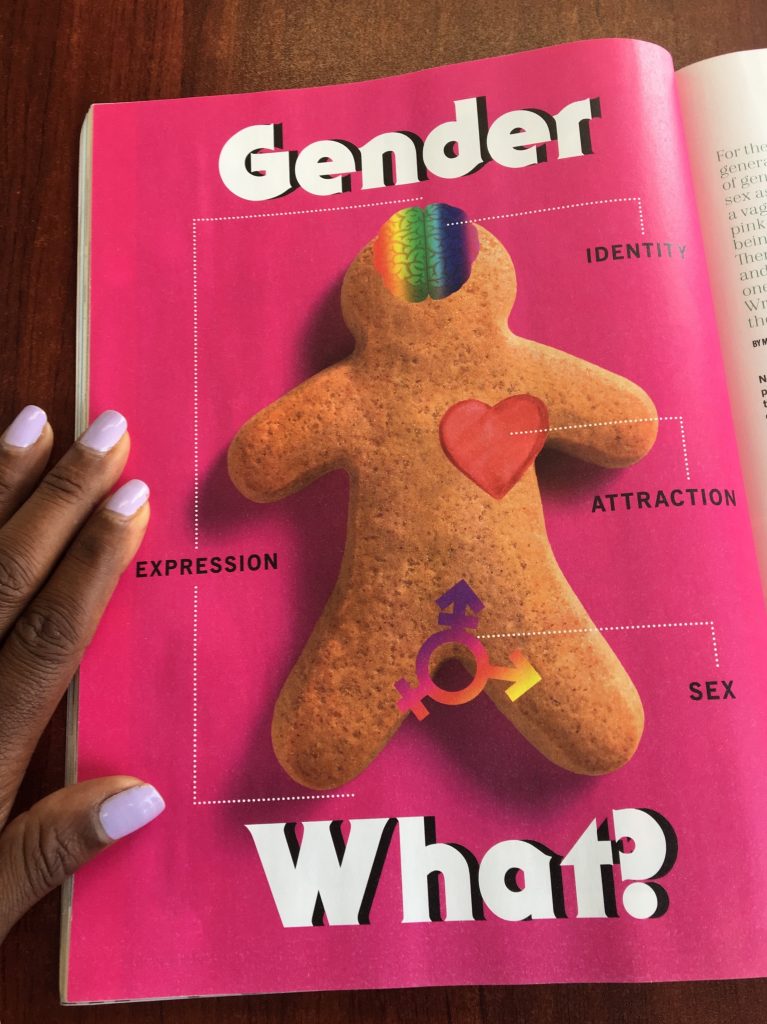

The first thing that grabs your attention about this album is the title. When I read about the album I was first amused and then really moved by the title Boet/Sissy. You see as an effeminate gay man, I know all too well the weight of the term Boet/Sissy. I’m also acutely aware of the venom that usually accompanies this phrase. Growing up in Xhosa culture (I believe this is the case in other black communities in South Africa) Boet/Sissy was, and to some still is, a derogatory term that is used to bash gay men, especially effeminate gay men. The phrase is directed at effeminate gay men for being men who “act” like women. So Boet (or in Xhosa Bhuti) represents the male side, and then Sissy of course represents the effeminacy. It is a term that is often used interchangeably with “talase” which is a word people call gay me. It is a term that suggests one has both male and female genitalia. So then Boet/Sissy and talase are used as derogatorily synonyms for each other. People who use these words as putdowns often don’t care about the “real” meaning of the words, but are only interested in using the words to shame and to hurt whoever is perceived to be of a different sexual orientation. With the risk of sounding too postmodern, Majola is reclaiming this phrase; he is taking back the power. For me, Majola uses the Boet/Sissy in a productive way, similarly to the ways in which we have reclaimed the word queer. The use of Boet/Sissy is also similar to the way academics and artists have found productive use of shame, shame associated with same-sex sexuality. Majola’s use of Boet/Sissy is a queer thing to do, therefore immensely political. The fact that the album is mostly sung in Xhosa, which means it is directed to a black audience, speaks profoundly of the politics Majola is engaged in. When I saw the name of this album, I immediately thought about the piece I wrote about the complexities of sexual identity and the Xhosa language. In the piece I try to come to terms with having no specific Xhosa words in everyday language to talk about the diversity of sexual and gender identity. This piece sparked a number of conversations over the radio, and it seems the conversation of sexual identity and language continues in a different form with Majola’s album.

In the beginning of the album, in the first interlude Majola is standing in front of a judge before he is sentenced to jail. So his first utterances in the whole album is “I stand in this court a man, fully aware that manhood is a narrowly defined subject within society.” This opening lines targets the narrow definitions of manhood, particularly black manhood that often positions black gay men as outside of manhood. And then Majola goes on to define what he thinks is a man. Although I like what he says, and I think that he is politically astute to issues of masculinity, I find the five interludes in the album interruptive.

After the first interlude Majola then proceeds to the first song, track number two. The track is named Khanyisa, and it starts with the birth of a boy named Khanyisa in 1985 (which incidentally is the year I was born). In the song he does this haunting repetition of “kwazalwa indodana” – a boy is born. As Khanyisa grows up, experiences life, trying to discover himself, he gets lost wondering through life. Khanyisa eventually meets a woman called Nobanzi who saves Khanyisa’s life. The friendship that Khanyisa has with Nobanzi restores him, as this woman loves him. The affection with witch the lyrics are delivered warms the heart. The song is almost homage to the relationship between black women and effeminate black gay men. I have these relationships. These relationships are what got me through high school. I would be nothing, nothing without the love and support of black women. The song sets the tone for the album in a way, as he deals with issues of light and darkness, getting lost and found, and eventually loving yourself.

The third track called Bawo – father – the word is also often used in reference to God. This song is an affirmation of the gay identity. Majola talks about a boy who is cursed out, really chased out by his father for falling in love with other men. Majola begs in this, asking why the father is rejecting the gay son, where will he go? What is this boy to do? There is a theme of redemption in this album, and in this song Majola then continues with the narrative of being lost and found. The gay boy who is cursed out by the father finds his way to the big city and his life spirals out of control. This is a powerful song that speaks to the lives of many lesbians, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex (LGBTI) young people who escape home because of abuse. The homophobia experienced by young people is sometimes so intolerable that they would rather live elsewhere with friends or on the streets. Majola begs, and pleads for acceptance in this song. The piano keys coupled with Majola’s voice especially as the track fades towards the end has an incredibly haunting sound. I feel like this song is also speaking to the difficult relationship gay men often have with their fathers. A relationship of course that is mediated by the culture of patriarchy which often renders the gay boy useless, not man enough, and therefore not a good son. Having never had a real relationship with my own father, I can relate to this song. Majola is really engaging us in a conversation about masculinity and what it means to be a father to a gay kid.

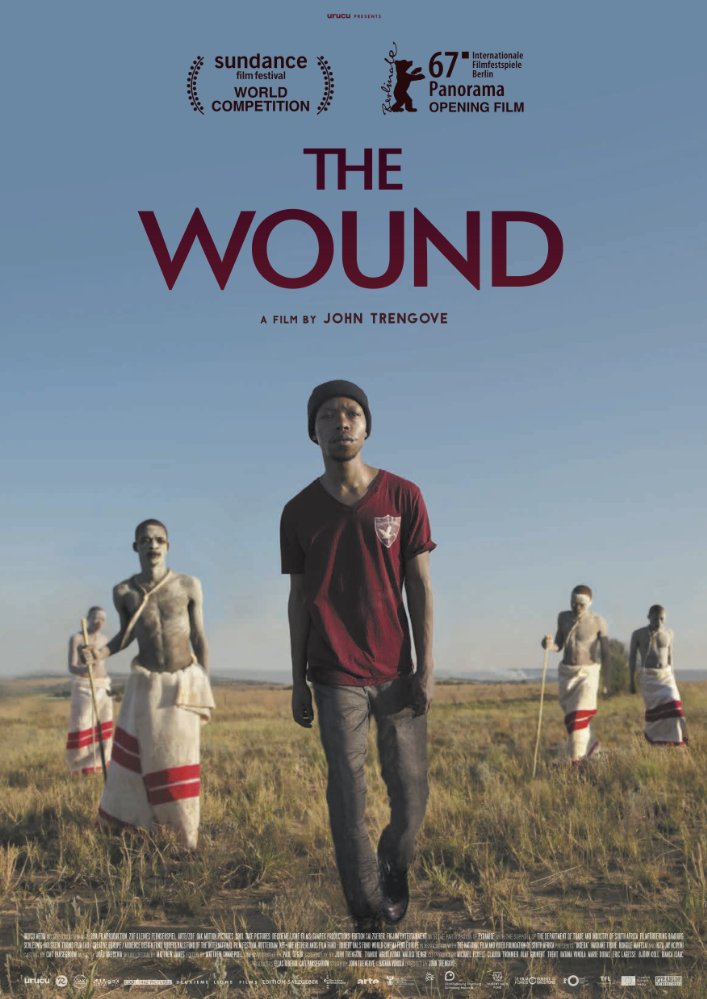

The Xhosa tradition of men going to the mountain for circumcision is a topic often treated with kid gloves. In the song Mountain View Majola rejects kid gloves and sings about falling in love and having a relationship on the mountain with another initiate. Interestingly, this is the only song on the album sung in English. Majola is bold because not only does he have a love affair on the mountain with another dude, he then sings about it. It is a kind-of middle finger to the homophobic Xhosa culture establishment. Because of what the mountain represents, it is the last place one would expect a same-sex love affair to flourish. But then again, maybe it is the ideal place seeing that it is only men walking around naked often with their penises hanging out. Although men are often all alone on the mountain, there’s often nothing erotic about that space, on the contrary, it can be dangerously homophobic. Maybe Majola is trying to prove to us that you can find love anywhere. I have to say though, getting a boner is not ideal on the mountain seeing that you are trying to heal a wound on the penis. This has got to be the first romantic song about a love affair on the mountain during initiation. The love experienced on the mountain is depicted as raiser sharp. Hot. And saucy. Majola talks about learning to love another man and understanding love. Singing about the lover on the mountain he states: “He was kind to me, patience a gift from him. I understood love, and how to make love from that initiate in the mountain.” Although both men experience great love, the love doesn’t survive beyond the mountain. This is definitely one of my favourite tracks on the album. Audacious. And just awesome.

The second interlude is track number five where Majola talks about being different and the journey to self-love. “I have always felt different to other males, stares of disdain, the name calling, distant affection from elder males and sometimes the violence inflicted on me confirmed that I was indeed different. The price I paid for being different is the excruciating loneliness I felt. Accompanied by guilt, shame and stigma, I overacted being a man and still wasn’t man enough to many … I was a secrete friend to some, and a secrete lover to many. I thought I was deserving of secrete validation, someone had to take a stand for me, and to my luck that someone turned out to be Me.” – Poetic.

Then there’s the title track where Majola captures the anxiety of growing up gay in the township. He speaks of the warnings people often give to visibly gay kids where they warn the young gay about their deviant sexuality. When I was growing up, people would say that you will grow up and become like uNokuku. Nokuku is an effeminate openly gay man that lived in New Brighton and was well know in Port Elizabeth and the surrounding areas. I believe Nokuku still lives in Port Elizabeth. Nokuku is what all young gay kids were warned against, he was used as an example of what one should never be. Nokuku had cult status as an openly gay person in Port Elizabeth, the only gay in the village kind-of status. Majola also references the other warning issued to gay boys that they must not become like the men who are on the Felicia Mabuza Suttle show. You will remember The Felicia Show had a number of episodes that were about members of the LGBTI community. The reference made by Majola of course means that he grew up in the 1990’s, when Felicia Mabuza Suttle was a big talk show host assisting South Africa through the transition to democracy. In the song Majola also makes a reference to “Adam and Eve and not Adam and Steve”. Homophobic heterosexuals often quote this line as if it’s the smartest line ever invented. The phrase ‘it’s not Adam and Steve’ is often accompanied by unintelligent smugness. This phrase needs to die and be buried. In the chorus of the song, Majola repeats “ndingu boet/sissy” –I am Boet/Sissy. He asserts and affirms himself in the song that he is he what he is, “and so what?”

Imbali is the next track. It is a track about love. It’s a lovely tune, but it doesn’t do to me what the other songs do. It is a soft song, and Majola holds himself back as he sings the song. Which I suppose is a good thing for an artist to be able to have restraint. It’s plain song for me, and it is preceded by some really marvellous tracks, so it doesn’t shine that much.

Throughout the album there are references to bible scriptures. There is an interesting way that Majola plays with church references. “Khulula ezombadada” is the line said to Moses by God that he needs to take off his sandals because he is standing on holy ground. Sondela is a slow jam. It is about two men making love; it is made that much sweeter by the Xhosa lyrics. Majola speaks of listening to the body parts of his lover, and how these body parts encourage him as they become intimate. The song is beyond courageous. Majola poetically croons about his manhood and the manhood of his lover and all this is done with a persistent haunting sound in the background. My heart skipped a beat when I heard this song for the first time, I had to go back and listen again to make sure what I heard was correct. I am not going to even pretend that hearing a black male artist talk about two men being intimate on a record in Xhosa is not a bit of a mind fuck.

In the third interlude Majola does not shy away to speak directly to the political situation of the African gay. He directs his words to those that prosecute gays all over the African continent. Majola states: “My sexuality is used as political fodder to dissuade from real political issues. Men whose crime is to love other men fill up prisons that should be filled by men who snatch bread from hungry mouths. Who rape and murder daughters and sons of this land. Love is one of the greatest virtues to be possessed by any human being. To be prosecuted for the courage to love is the highest crime committed against life itself.”

After the third interlude there are three tracks that are similar in mood, Ndindedwa, Luthando, and Andizoncama. It is in these tracks that you hear the influence of church or choral music. Although the influence of church music, particularly black Methodist, is felt throughout the album, there’s something about these three tracks for me that really captures that essence. In the title track Majola does make a reference to the Methodist church where he carries the cross in the church procession, but is afraid when he leaves the church that there is a boy that will taunt him on the way home without anyone there to stand up for him. The influence of church music in the album is undeniable. Of course Majola follows in the footsteps of many black artists whose artistry has been “honed” in the church.

Interlude number four is all about loving men. Majola states: “I love men, I love the feeling of being held by another man. In another man’s arms I find comfort, safety, healing, escape, release, pleasure, and unspeakable joy.” These words reminded me of the beautiful piece written by Fumbatha May called a love letter to the black man in the Mail and Guardian. Fumbatha May writes a loving and inspired piece. After speaking these words in the interlude, Majola proceeds to one of the two up-tempo songs on the album. The name of the song is Zithande – Love yourself, which is really an anthem for gay people to practice self-love. Living in a world that is dominated by heterosexist institutions, it becomes political for LGBTI people to love themselves. Majola sings “funda ukuzithanda” – learn to love yourself. In this track I find Majola’s lyrics affirming and reassuring. The way he articulates ‘”learn to love yourself” one can’t help but think of the message of black consciousness, where black people are made to realize that loving themselves is a political act. So in the same way that black love is an act of resistance so is black queers loving themselves.

In queer circles, especially black queer circles Simon Nkoli need no introduction. In the song Simon Nkoli, Majola praises Simon for his activism in the anti-apartheid struggle, the gay liberation struggle, and also his involvement in HIV/Aids activism. Simon Nkoli was a hero and Majola gives him the honour and respect he deserves. In this song Majola gives Simon Nkoli the same reverence that Madikizela-Mandela, Robert Sobukwe, Steve Biko, and Nelson Mandela receive in Thandiswa Mazwai’s Nizalwa Ngobani. Also in this song Majola continues his narrative of darkness and light as he speaks of Simon Nkoli as a light in the darkness. And for many black LGBTI people, Simon Nkoli was just that, a light. The up-tempo beat gives the song a celebratory feel, celebrating a man’s life spent trying to conscientise South African society. This album will now be part of the archive of black queer lives in South Africa, and the fact that it pays homage to legendary people like Simon Nkoli makes it even that much more poignant.

The fifth interlude is the sentencing of Majola from the judge who he stood in front of at the beginning of the record. The judge then proceeds to read his sentencing.

The closing track Majola sings about Ikhaya lam – my home. In this track he goes back to his melancholic sound that was interrupted by the two previous tracks. Interestingly, the question of home has been a topic of conversation within my friendship circle. I was born in Port Elizabeth. Many of my friends come from diverse backgrounds and different cities from all over the world, and the question of what is home is always a topic of discussion. Although I call Cape Town home, it is never without qualification. Majola asks for his home to take care of him, to protect him from the world. Home for Majola is a place where he finds safety, a place that offers protection. In this song Majola concludes with the narrative of darkness and light, talking about wanting protection from the darkness of the world. Again, it is hard to miss the biblical undertones. Bible references and all, Majola has given us an amazing piece of art. The album is a bold queer statement. The subject matter of this album is about what it means to be black and gay and live in South Africa. Majola takes us on a journey of a black gay boy, negotiating manhood, falling in love with other men, and experiencing rejection from family. Although one can claim universality in the experiences described by Majola in this album, this is an album about the life experience of a black gay boy. Majola bares himself and speaks his truth, and in the process holds a mirror for me to see myself and I am grateful for it.