We are weeks away from the first anniversary of the horrific murders of University of the Western Cape student Jesse Hess, and University of Cape Town student Uyinene Mrwetyana. Leading up to the first anniversary of their deaths, we have been overwhelmed with news of the brutal murder of Naledi Phangindawo by a man wielding a knife and an ax.

While digesting this news we were confronted by the news that Tshegofatso Pule was murdered by her partner who stabbed her and hung her from a tree. She was 8 months pregnant. There was then another report of a women who was stabbed and dumped in an open field in the Eastern Cape. Her boyfriend was arrested for the murder by the Mthatha detectives.

In KwaZulu Natal, Zamadeyi Goodness Ngaleka, was shot dead by her husband, and then he turned the gun on himself. We are hearing about these horrific stories while we are under a Covid-19 induced lockdown, where there were reports that the police received a record number of calls reporting Gender Based Violenceduring the lockdown. The stomach churns as we read, as we hear, as we bear witness to the violence and the murder of women by men in South Africa.

Reading about these murders, seeing hashtags demanding justice on social media, and knowing that this is a repeat of a cycle one has witnessed before sits heavy on the heart. Being alive right now and absorbing the news of all this violence is traumatic.

In August last year, with the murders of Jesse Hess and Uyinene Mrwetyana, words seemed so banal. In the current moment as well, words seem so trite, so vacuous. It feels like everything has all already been said, and that words may not be enough. In all the despair, what do we do?

I find courage in the words of the late Toni Morrison, speaking about dark times, dark times like the ones we find ourselves in this country. Morrison writes: “This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.” So through the hurt, through the powerlessness, we do language. We speak, and we speak truth to power – we speak truth to patriarchal power.

My high school going cousin recently gave birth to a baby girl. She herself is really still a child. Truth be told she doesn’t have the means to take care of the baby. My aunt, the grandmother is helping. Like usual, the women are the caregivers. In 2017, it was reported that 62% of birth certificates issued in South Africa had “no information on the father”. This is the social landscape of South Africa.

While I am relieved the baby is healthy, all I have been thinking about since the child’s birth is her trajectory in this country. To be born poor, to a teenage mother, in a country with what seems like a careless government. To be born a girl in a country with war-time-like rape statics. I ask myself what are her chances in this society?

All conversations of Gender Based Violence need to take into account the social structures that make violence possible. Indeed, inevitable. With Gender Based Violence we need to start at the beginning. To echo Kagiso Molope, in order for us to really end Gender Based Violence, the sexual assaults on women, and the general brutality on women’s bodies, we need to raise boys differently.

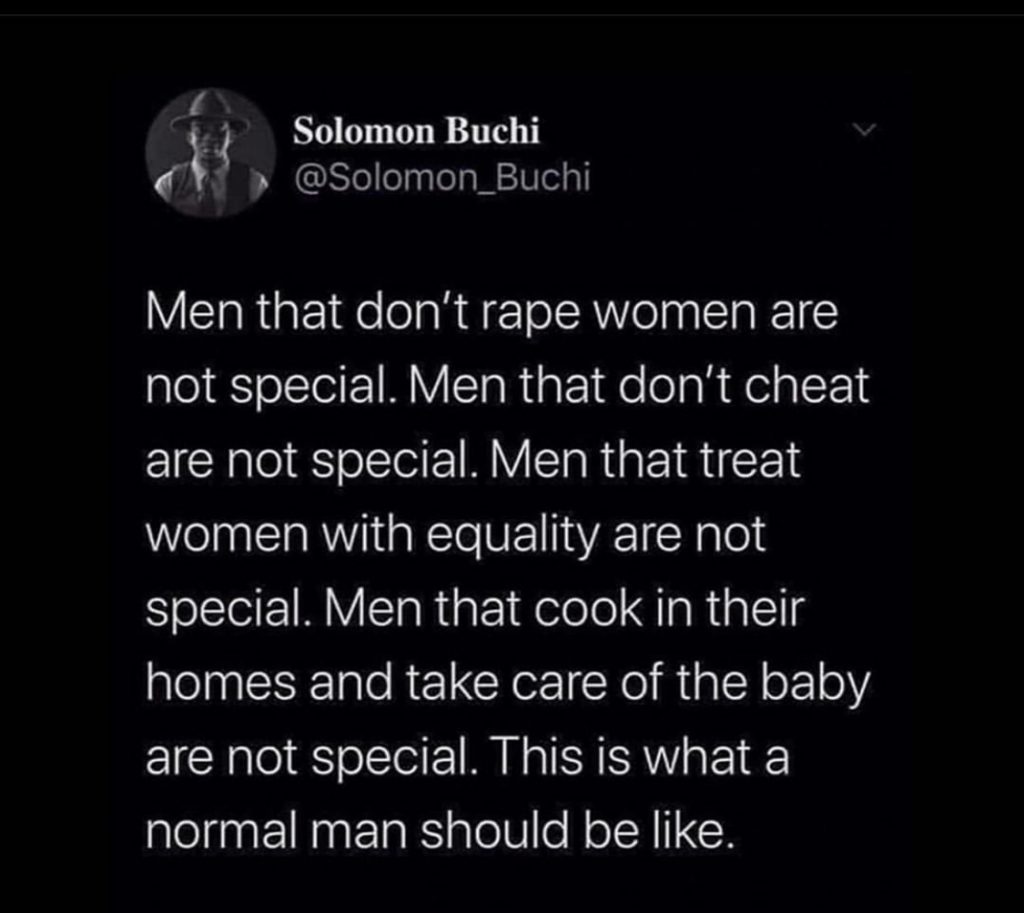

The men who become rapists were once boys who were taught to think very little of women. Boys are born and raised into a social language of violence, where the humanness of women is less than that of men. As a society we need to rethink, and redo, the way we raise boys.

I can’t help but invoke bell hooks here, “The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves. If an individual is not successful in emotionally crippling himself, he can count on patriarchal men to enact rituals of power that will assault his self-esteem.”

From the beginning boys are taught a very limited palette of emotions, which often don’t include empathy, vulnerability, healthy demonstrations of sadness, tears, and solution of problems that don’t include violence. In homosocial settings, pressured by other men, men are forced to outperform each other at manhood. Often, the demonstrations of manhood are wrapped up in a valorised culture and language of violence where women become collateral damage.

Gender inequality, like racial inequality, is difficult to change because it is structural, and so we need to stop individualizing the gender problem. The gender problem is a systemic problem. For example, there is a horrible tendency in South Africa to walk on eggshells when it comes to religion. Religion is almost beyond reproach in this country. Yet some forms of religion clandestinely endorse Gender Based Violence.

Take the scriptures; I Timothy 2:12 “I do not permit a woman to teach or to exercise authority over a man; rather, she is to remain quiet.” There’s also, Mark 10:12 “And if she divorces her husband and marries another, she commits adultery.” Who can forget Ephesians 5:22-24 “Wives, submit to your own husbands, as to the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife even as Christ is the head of the church, his body, and is himself its Saviour. Now as the church submits to Christ, so also wives should submit in everything to their husbands.”

I use these scriptures to make obvious the larger system that has built and upholds gender inequality. While I use Christianity as an example here, this pertains to other religions as well. We can’t have honest conversations about Gender Based Violence without engaging the structures that make violence possible.

“Culture” is also similarly constructed as beyond reproach in this country. By culture I mean the practices that people engage in that are attached to their language groups and/or ethnic identities. Like, Xhosa culture, Venda culture, Afrikaans culture. The violence committed in the name of culture on women in South Africa is danced around by many.

The horror of the way that culture is wielded in the subjugation of women in South Africa is exemplified by the Jacob Zuma rape trial, where Fezekile Kuzwayo was demonized. We dance around practices such as Ukuthwala. Often, the “protection” of culture from imperialism is invoked as we count the mutilated bodies of women and girls in South Africa.

Often, we speak of imperialism, colonialism, and apartheid as if colonialism and apartheid didn’t affect women in this country. When hard evidence shows us that women were adversely affected by colonialism and apartheid. Residue of which is the gendered power structures that remains with us.

As demonstrated by Kopano Ratele in his book Liberating Masculinities, there is a particularity to black men’s experiences and their inhabiting of masculinity and manhood. Here, in talking about black men I am including coloured and Indian men and other “men of colour.” I take my cue from the words of Koleka Putuma’s Collective Amnesia, particularly the poem on Black Solidarity, where she writes, “Black solidarity at the expense of a black womxn’s anything is a farce, a rip off.”

Putuma’s words remind us of the Rhodes Must Fall and the Fees Must Fall student movements where gender issues, queer issues were purposely undermined by the men in the student movements as unimportant and divisive. Imagine, women and gender non-conforming people asking for their humanity to be recognized, to be taken into account, was read as divisive in student movements that were calling for “decolonization” of the university.

This warrants us to question the place of gender, of non-normative genders, and of sexuality in the “decolonial” moment? Can we talk about “decolonizing” without talking about Gender Based Violence?

No. We can’t.

Unless decolonization takes seriously gender inequality, the ideas on decolonization are half baked.

While we were reeling from the news of Gender Based Violence and murders over the past couples of weeks, there were reports of the violent murder of Kirvan Fortuin, a gender non-conforming queer person from Cape Town. Fortuin was allegedly murdered by a 14-year-old girl in a homophobic attack. 14 years old. Kirvan Fortuin’s death, a person who challenged society’s understanding of gender, particularly manhood, in the midst of the murders of other women, necessitates that we recognize the connections, make the links, to understand the operations of systemic violence brought to different kinds of women, gender non-conforming peoples, and girls, in South African society.

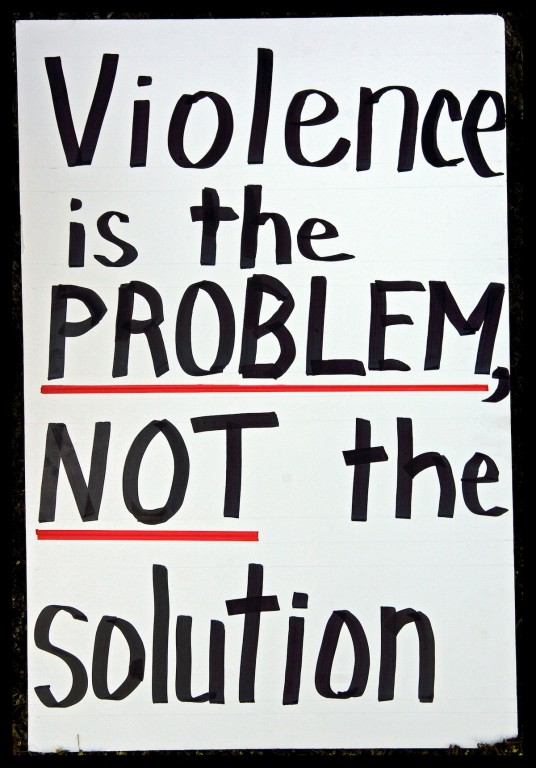

Gender inequality is a systemic problem, therefore solutions to gender inequality need to address the system. All of us are implicated in finding solutions to Gender Based Violence, to sexual violence, and the ongoing mutilation of women’s bodies. When I say we are all implicated, I mean that ALL men are implicated.

It was striking in the media reports of the murders of Naledi Phangindawo and Tshegofatso Pule how there were “witnesses” and/or “bystanders”. There are so many questions about these witnesses and how they are implicated in these heinous crimes. While I am not sure what “witnesses” means in these reports, it does point to the many ways people are complicit and therefore implicated in the murder of women.

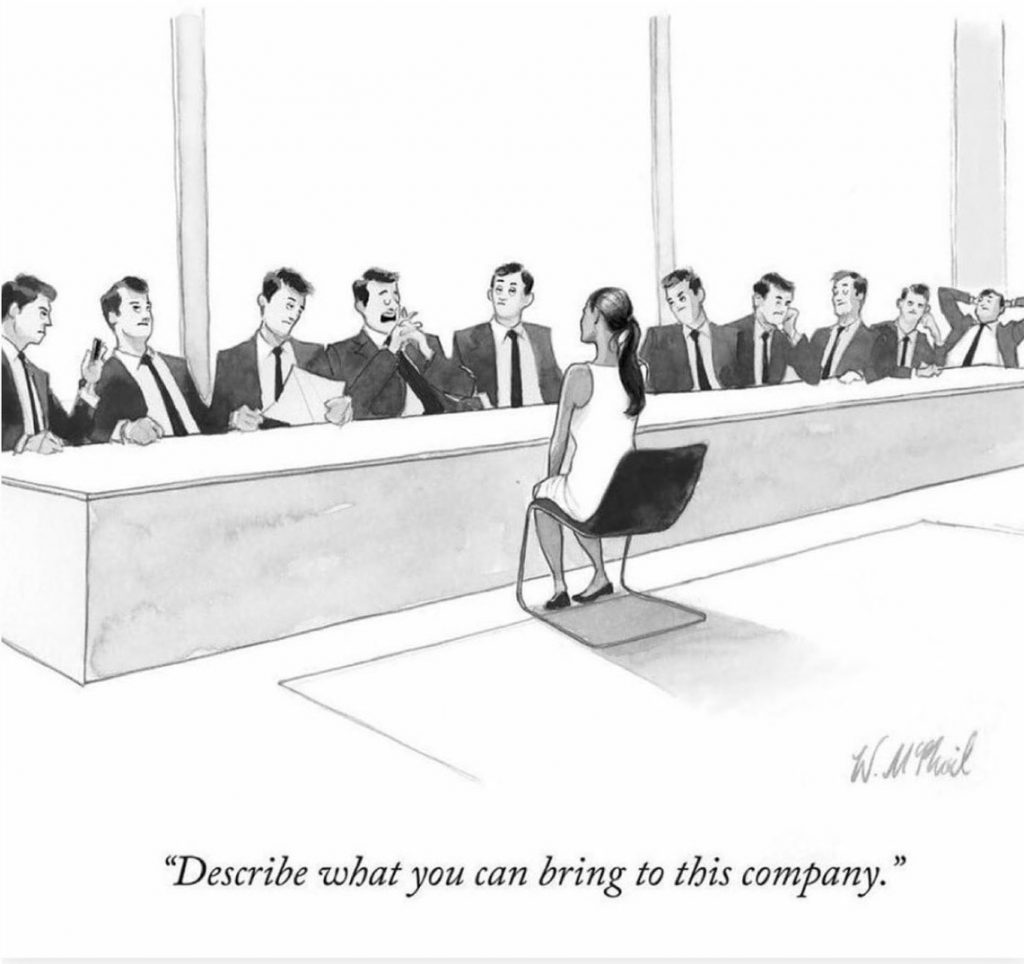

South African institutions are implicated in the ways they perpetuate gender inequality in hiring decisions, undermining women’s positions, and participating in mansplaining. In the university environment, the fact that gender as an area of academic inquiry is marginalized speaks volumes on the seriousness the academy itself takes Gender Based Violence. Gender is not only the business of the women’s studies department, it is the business of the university, it is the business of commerce, it is the business of architecture, it is the business of law, it is the business of the health science.

Similarly, with government, gender politics and policy are not solely the mandate of the Department of Women, Youth and Persons with Disability, but the business of all sectors of government. Government response to Gender Based Violence is to invoke a distancing language of “we condemn violence”, as if it is not part of their duty to be hands on in the fight for gender justice. President Ramaphosa speaks as if the “enemy” is elsewhere, when the state is complicit in the sloppy handling on gender-based crimes and murders.

Until it is recognised that gender justice is the responsibility of all of us, and leadership in corporate, government, universities, and other institutions takes the appropriate-yet-radical steps, we are not going to solve the gender inequality in South Africa.

The fight for gender justice is a fight for freedom. It is a fight to achieve freedom for women, and those who are strangled by the patriarchal gender order. As South Africans who are living in post-apartheid South Africa, we need to continuously make the links between freedom and gender justice. In many ways, in post-apartheid South Africa, we tend to have narrow ideas of freedom. The fall of apartheid was not just for cisgender men to be free; it was so that ALL South Africans can be free.

In thinking about freedom for all people, including women, it is useful to invoke Martha Nussbaum’s idea about capabilities as fundamental entitlements. The idea of capabilities differs from the narrow libertarian idea of freedom from state interferences. Capabilities is about freedom to be able to live, a freedom to pursue your dreams and flourish. I find Martha Nussbaum’s articulations on “Life” and “Bodily Integrity” being essential in enabling not just Human Rights, but Human Capabilities useful. According to Nussbaum:

“Life. Being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length; not dying prematurely, or before one’s life is so reduced as to be not worth living.”

“Bodily Integrity. Being able to move freely from place to place; to be secure against violent assault, including sexual assault and domestic violence; having opportunities for sexual satisfaction and for choice in matters of reproduction.”

In post-apartheid South Africa men experience women’s liberation – the push for gender justice, as their disempowerment. Men need to ask themselves, what am I without misogyny? What am I without power to dominate women? To end, I would like to invoke Toni Morrison again, “If you can only be tall because someone’s on their knees, then you have a serious problem.” And South Africa, we have a serious problem on our hands. A problem that demands all men’s hands on deck, as we overhaul dominant and violent tropes of manhood and masculinity.