Last month, January 2019, I attended the two day “Gender, (Inter) Generation, and Negotiating Power in Families Workshop” at the University of Cape Town (UCT). At the end of day one of the workshop, Professor John Comaroff, the distinguished professor of African and African American Studies and Anthropology at Harvard University (of Jean and John Comaroff fame) delivered the closing remarks. I was struck and inspired by Prof. John Comaroff when he closed the workshop as he spoke about hope. He said that it sounds like a cliché, and maybe it is, but in these social and economic tumultuous times we must keep hope alive as we struggle towards lasting solutions to the ills of our country, indeed the world.

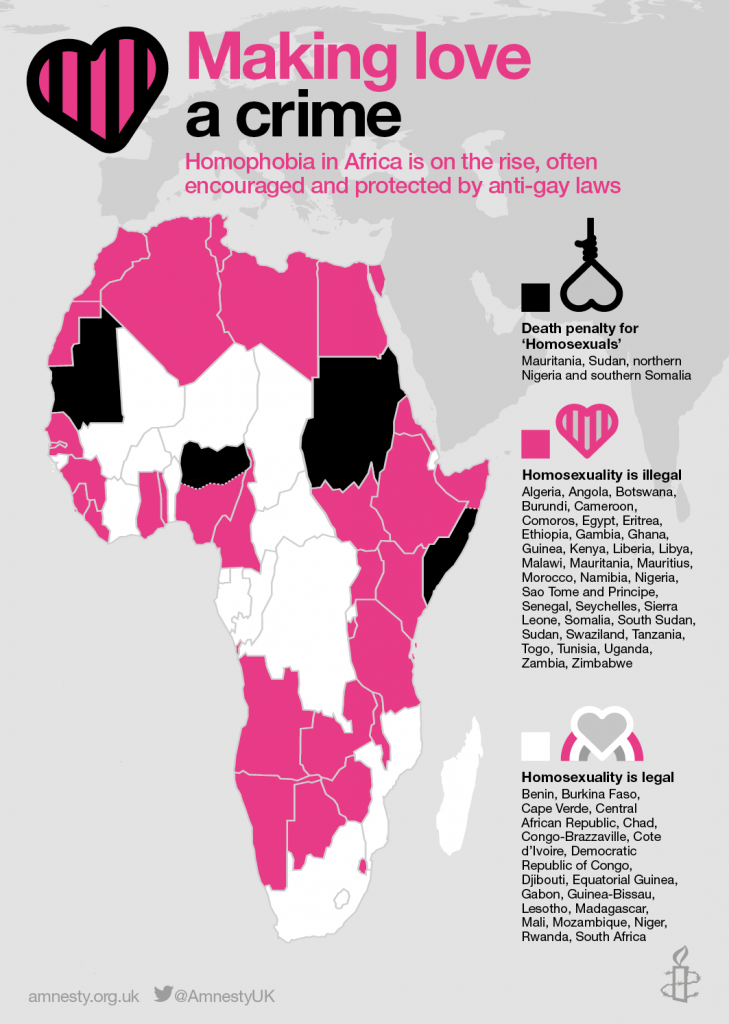

Comaroff’s spoke about hope just days before Angola was to announce the decriminalisation of same-sex acts and the banning of discrimination based on sexual orientation. The news was widely welcomed, and people around the world rejoiced for the progressive movement that Angola was taking in acknowledging the humanity of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Angola.

As I was reading about the decriminalisation and the banning of discrimination based on sexual orientation, I kept on thinking about John Comaroff’s words about hope, and how Angola’s move instils a sense hope with regards to LGBT politics on the African continent. Angola’s progressive stance comes months after Tanzania was reported to have searched for and rounded up LGBT people in the country. There were reports that people were being brutalized and tortured and thrown into jail. Many LGBT people, and LGBT activists in Tanzania were reported as going into hiding fearing for the lives.

The LGBT victory in Angola is not insignificant, considering the recent troubles in Tanzania; considering the unsuccessful introduction of the Anti-Homosexuality Act 2014, a bill that was widely known as the “kill the gays bill” in Uganda; considering the targeting of transgender people by the Trump administration in the United States; considering the prosecution of LGBT people by the Nigerian government; considering the continuous murder of transgender people in Brazil; considering the homophobia and physical violence still faced by LGBT people in South Africa – despite the fact that same-sex marriage is legal here; considering the rounding-up and torture of LGBT people in Russia; considering the rounding-up and torture of LGBT people in Chechnya; considering the reported story of a man who was raped, reported the rape to officials and was then subsequently charged with same-sex relations under the penal code in Tunisia, a code that carries the penalty of 4 years in prison.

Angola is a beacon of hope in a world that is adamant about the brutalisation of LGBT people. While it might seem insignificant looking at the widespread persecution of LGBT people around the world, it is significant. It is a move in the right direction towards justice and human rights. Angola provides a progressive roadmap for the other 33 or so African nations that still criminalise same-sex intimacies. In Mauritania, Sudan, Northern Nigeria, and Southern Somalia those found guilty of same-sex intimacies potentially face the death penalty. Hope, then, is important in the troubled times we live in, times of increased fascism (United States anyone) and authoritarianism (did someone say Brazil), where human rights are undermined in the most disturbingly glaring ways.

Of course, one has to be cautiously optimistic because we know that decriminalisation and the banning of discrimination based on sexual orientation is only addressing part of the problem. Decriminalisation changes laws, but not hearts: there is much work to be done to transform families and communities where LGBT people actually live and experience everyday harassment, discrimination and sometimes violence.

While recognizing the limited effect that a change in the law will have on the lived reality of LGBT people, we can’t underestimate how changing of laws creates avenues for citizens to have recourse when they are victimized. The change of laws in post-apartheid South Africa has had profound effect on the sense of belonging of LGBT citizens in South Africa. The recognition afforded to LGBT people by the Constitution of South Africa became a catalyst, first for changes in the law, and then (and more gradually) changes in attitudes. This culminated, as it were, in the adoption of legislation recognising same-sex marriage. So, the changing of laws is a fundamental step in the process of ensuring the human rights and the human dignity of LGBT citizens. It is such an important step, that Pierre De Vos, convincingly argued that the Constitution “contributed to the constitution of lesbian and gay identity” in democratic South Africa in the aptly titled paper, “The Constitution Made Us Queer.”

It is impossible to speak about the decriminalisation of same-sex intimacies in Angola, or any other African state for that matter, without talking about the impact of colonisation and the laws created by imperialists government on the lives of LGBT Africans. Angola, a former Portuguese colony, adopted anti-sodomy and other homophobic legislation from the Portuguese settlers. And like Mozambique, another African state formerly colonised by the Portuguese, Angola is now slowly transitioning to be a place where LGBT people and their ways of loving are recognised by the law as legitimate forms of intimacy.

It is striking that it is formerly British colonies (Tanzania, Nigeria, and Uganda are three who have made headlines in recent years), that have been historically particularly cruel towards LGBT people. This probably tells us much about the legacies of puritanical values of Victorian Britain with restrictive laws created by settler colonists, and how they have been adopted by native Africans against other native Africans with detrimental consequences. In this context, the progressive movement that Angola has embarked on provides an opportunity for a different narrative for LGBT Africans, a narrative that Africans themselves can be at the centre of constructing.

LGBT rights are often advanced by the tireless work of LGBT advocacy groups and non-profit organisations lobbying and pushing for change. Groups like Iris Angola Association (Associação Íris Angola), that is now legally operating in Angola, are visible and empowering LGBT people. The kind of work done by Iris Angola Association can only strengthen as the populations they are working with are no longer constructed as “breaking the law.” One of the biggest impacts that decriminalisation does is to afford LGBT organisations space to do the kind of work that is necessary to empower LGBT youth and LGBT communities. This is important in ensuring a better livelihood for LGBT people, and to cultivate a culture built on the respect of human rights.

Engaging with the developments in Angola, I am energised. I am filled with hope of a better continent, indeed world, for LGBT people. I am given strength to continue the fight for social justice for LGBT people. I am encouraged to continue engaging those in power who have not seen the light yet, that LGBT rights are human rights. I am filled with hope that slowly our societies will see that until ALL LGBT people are free everywhere, there can never be real LGBT freedom anywhere.