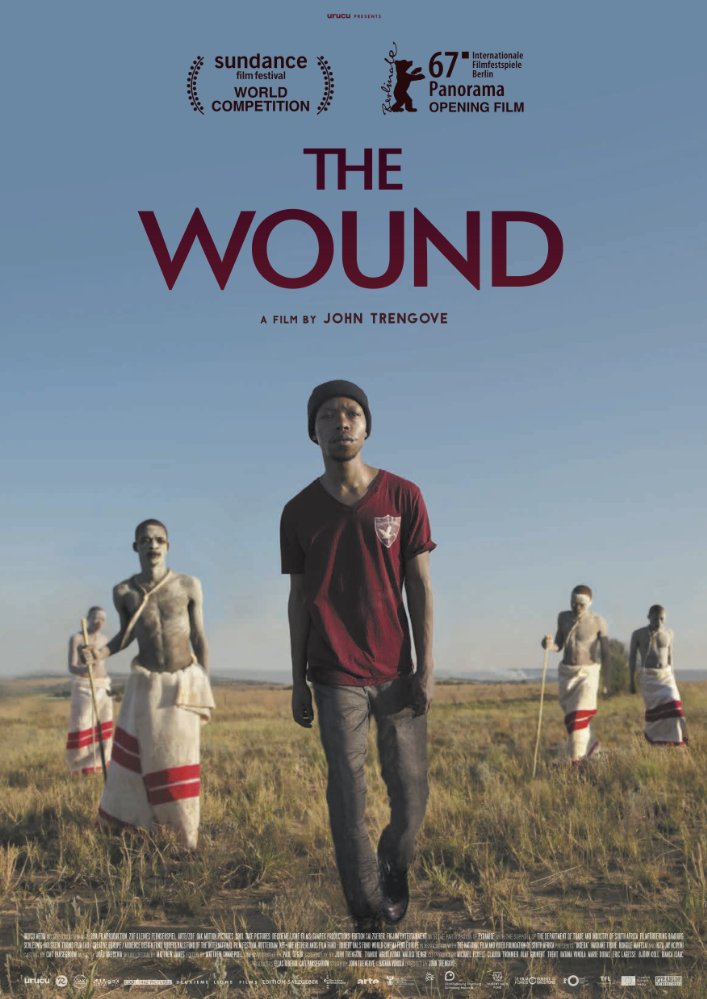

To say that the movie, Inxeba (the wound) is controversial is to put in mildly. I have written about my experience of seeing the film, and how moved I was by the movie. The film has resurfaced the conversation about Xhosa initiation rites. I say “resurfaced” because the conversation about Xhosa initiation tradition is an ongoing conversation. Both Thando Mgqolozana, one of the writers of Inxeba, and Nakhane, one of the actors in the movie, wrote about the initiation process or some aspects of it in their respective books. Thando Mgqolozana wrote A Man Who Is Not a Man and Nakhane wrote Piggy Boy Blues. So Inxeba, the movie, uses a different medium to contribute to an ongoing conversation about different initiation experiences.

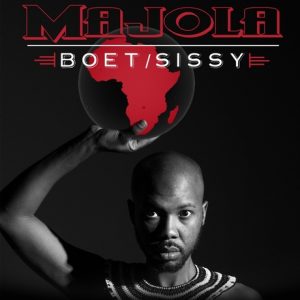

Majola’s album Boet/Sissy is also part of this ongoing conversation. In Boet/Sissy Majola sings about life as a queer Xhosa man. I wrote a review of the album as I was also moved by Majola’s work. It is worth repeating partly what I wrote on the review of the song Mountain View, where Majola sings about falling in love on the mountain:

“The Xhosa tradition of men going to the mountain for circumcision is a topic often treated with kid gloves. In the song, Mountain View Majola rejects kid gloves and sings about falling in love and having a relationship on the mountain with another initiate. Interestingly, this is the only song on the album sung in English. Majola is bold because not only does he have a love affair on the mountain with another dude, he then sings about it. It is a kind-of middle finger to the homophobic Xhosa culture establishment. Because of what the mountain represents, it is the last place one would expect a same-sex love affair to flourish. But then again, maybe it is the ideal place seeing that it is only men walking around naked often with their penises hanging out. Although men are often all alone on the mountain, there’s often nothing erotic about that space, on the contrary, it can be dangerously homophobic. Maybe Majola is trying to prove to us that you can find love anywhere. I have to say though, getting a boner is not ideal on the mountain seeing that you are trying to heal a wound on the penis. This has got to be the first romantic song about a love affair on the mountain during initiation. The love experienced on the mountain is depicted as raiser sharp. Hot. And saucy. Majola talks about learning to love another man and understanding love. Singing about the lover on the mountain he states: “He was kind to me, patience a gift from him. I understood love, and how to make love from that initiate on the mountain.” Although both men experience great love, the love doesn’t survive beyond the mountain. This is definitely one of my favourite tracks on the album. Audacious. And just awesome.”

What I want to demonstrate here is that there are some Xhosa men, particularly queer Xhosa men who have been vocal and engaging in a conversation about Xhosa initiation rites. Mgqolozana, Nakhane, and Majola have all produced work that speaks to Xhosa initiation rites. These creative works highlight the different experiences of boys journeying to manhood. Inxeba is a wonderful contribution to this ongoing conversation.

Before I watched the movie, I had seen on social media and newspapers that there were people, particularly Xhosa men who were against the movie. Many have been upset because the movie exposes Xhosa initiation rites “secrets.”

Nakhane has received death threats over the movie. As people living in a democratic South Africa, people are allowed not to like the movie and express disagreement over it, but death threats over the movie are alarming. Ironically, the death threats towards Touré reveals the very toxic Xhosa masculinity that is on display in the movie. The violence that Touré is being threatened with is linked to the violence that often accompanies the making of Xhosa men. You have to appreciate the fucked-up-ness of our society where death threats are so nonchalantly issued and treated as normal when you disagree with someone.

Even the Xhosa King Mpendulo Zwelonke Sigcawu has weighed in on the “debate” over the movie calling for a boycott of the movie. It is hard to imagine that King Sigcawu has seen the movie yet because he is in the Eastern Cape and the movie has had limited screenings, and none of them were in the Eastern Cape. This means that the King has not seen the movie, but he is calling for a boycott of the movie.

According to the Times, the Xhosa King and other traditional leaders will submit a complaint to the Film and Publication Board and National Heritage Council about the film, apparently, the film is “too graphic.” As someone who has seen the movie, I wonder which part of the movie is “too graphic”? Is it the bum sex scene? Is it the circumcision scene? Or is it the scene at the end of the movie?

According to the Times, the King has said that the movie will instigate “the wrath of ancestors. Attacking and insulting this custom is an attack to our ancestors.” This is interesting because the King does not seem to wonder about the “wrath of the ancestors” when queer Xhosa boys are physically and sexually assaulted when they go through initiation. Where is the talk of the “wrath of the ancestors” when Xhosa boys come back from the mountains in body bags. I am sorry King Mpendulo Zwelonke Sigcawu but the “wrath of your the ancestors” is very selective, not to mention condones homophobic violence.

I find that the outrage over the movie is outward looking. People are preoccupied about how we, Xhosa people, will look to the “outside” world. Yet, the call of this movie is for us, Xhosa people, to look at ourselves. It is a call to maybe rethink some aspects of our culture. It is a call to think about – what does the things we do do? While it is important that we respect and take pride in our Xhosa customs and traditions, we can’t do so blindly. As people, we need to question and call out harmful practices, even if they have a long lineage.

The responses calling for the boycott of the movie, and the death threats on Nakhene’s life, is all about silencing. The responses are about having control over the narrative surrounding initiation practices. The initiation process is shrouded in secrecy. It is mythologized. One is forbidden to talk about it in fear that “secrets” will be revealed. As Xhosa men, we are held to ransom with the silence. The silence is powerful. At times the silence enables destruction. The silences surrounding the initiation process reminds me of Michel Foucault, who wrote:

“Silence itself–the thing one declines to say, or is forbidden to name, the discretion that is required between different speakers–is less the absolute limit of discourse, the other side from which it is separated by a strict boundary, than an element that functions alongside the things said, with them and in relation to them within over-all strategies. There is no binary division to be made between what one says and what one does not say; we must try to determine the different ways of not saying such things, how those who can and those who cannot speak of them are distributed, which type of discourse is authorized, or which form of discretion is required in either case. There is not one but many silences, and they are an integral part of the strategies that underlie and permeate discourses.” (The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, p. 27).

Indeed, there are many silences surrounding the Xhosa initiation process and Inxeba breaks some of that silence. We need to pay attention to the silences that exist between all the things that are said about the process of making Xhosa men. In the loud elevation of pride in tradition, there is the silencing of the horrific aspects of our cultural traditions. In the blind and vigorous holding on to “Xhosaness”, there is the silence on the destruction of young people’s lives. While there is noise about preparing men for heterosexual manhood, there is silence about homosexual desires. There is silence over the production of misogyny in the initiation process. There is silence over the botched circumcisions that are reported on every “circumcision season.” There are silences about the particularity of the initiation experience for queer Xhosa boys.

Instead of calling for a boycott of the movie, we should really take this opportunity as a space for conversation. The movie is a conversation starter for us to engage with each other, and not just about same-sex love between Xhosa men, but the initiation process itself. We should see this movie as a mirror held up to our faces so that we, as Xhosa people, can look at ourselves. Future generations of Xhosa people, specifically Xhosa boys will be grateful that this moment happened.