Author: Malaika Wa Azania

Written by: Lwando Scott

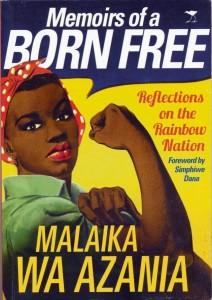

When I saw this book, I knew I had to read it. I have a thing for clever book tittles and I love smart book covers. There’s even a book covers archive that I visit more often than I should. Memoirs of a Born Free touches on subjects that almost every black South African will have experienced. Reading this book I could see myself and I could remember the experiences I’ve had navigating South African society. I could see the lives of thousands other young black people who have travelled a similar road as Maliaka Wa Azania.

Firstly I love how Setswana is peppered throughout the book. The use of the African language in this book is reminiscent of the way we speak; it is the way black people converse in everyday life. The code switching between English and multiple vernacular languages that is present in my everyday conversation with other black people is very much present in this book. Malaika Wa Azania succeeds in translating everyday reality, the everydayness of her life into paper and it is such a pleasure to read. She also tries to convert certain vernacular phrases like “njengamathe no lwimi” into English “inseparable as a tongue and saliva” and obviously it doesn’t sound as punchy in English as it does in the vernacular, but the message is sent.

Malaika Wa Azania’s battles with navigating white spaces and white culture is a recurring theme in the book. She addresses her dealings with white supremacists culture when she talks about how when she attended Melpark Primary School, which is a former Model-C school with predominantly white students and white teachers, and felt like part of her was left in the township of Meadowlands Zone 8. That part of her was not welcomed in this white establishment.

What connects me to this book is also what frustrates. On the one hand I am glad that I have someone who understands what it means to be young and black in South Africa, but it also means that there’s something horribly wrong with social structure of South Africa that young black people are experiencing similar racial and class problems. Black people navigating predominantly white spaces are constantly complaining about the need to assimilate in order to be taken seriously, or seen as part of institutions in South Africa. The irony of-course is that assimilation often results in just as much alienation and humiliation as non-assimilation.

Reading this section of the book reminded me of three studies that have been conducted at the University of Cape Town about black students struggling to navigate the former whites only university. These are the studies:

- “Like that statue at Jammie stairs”: Some student perceptions and experiences of institutional culture at the university of Cape Town. By Melissa Steyn and Mikki van Zyle (1999).

- Not naming Race: some medical students’ perceptions and experiences of ‘race’ and racism at the Health Sciences faculty of the University of Cape Town. By Zimitri Erasmus and Jacques de Wet (2003).

- “Coming to UCT: Black students, transformation and the politics of race.” HUMA Seminar presented by Dr. Shose Kessi (2014).

All of these studies point to the alienating and humiliating nature of former whites only institutions that are refusing to transform and culturally embrace the post 1994 student body. What Malaika Wa Azania’s experiences growing up as a “Born Free” is indicative of the experiences that black students on different schools and campuses around the country.

The alienation depicted in this book is worsened by the humiliation of poverty. Although Malaika Wa Azania writes about “drawing strength from poverty”, it is painful to be reminded about one’s poverty on a daily basis at predominantly white schools by whites and sometimes black kids from middle class homes.

While reading the book I had a laugh out loud moment when Maliaka was insensitive to a school teacher who was crying in front of her class over her dog that had recently died by laughing at the woman’s tears. Malaika couldn’t understand why someone would cry over the death of a dog, so different the worlds that Malaika and her teachers and fellow students lived in. The relationships white people have with their pets was humorous to a township kid who grew up with stray dogs. In the township even yard dogs never reduced their owners to tears when they died.

I personally identified with the struggle for education in Malaika Wa Azania’s memoir. She passionately discusses the impossible task of trying to get a decent education in this country if you are poor or from a working class background. The odds are against you in every possible way, and reading this book, I couldn’t help but think of my own quest for education which has not been easy, particularly when I was finishing matric and about to starting university. Just like Malaika Wa Azania, my mother lost her Pick n’ Pay job in my matric year, and the future was so uncertain at that time. I was anxious about a future that could possibly never be because all my hope was in getting a decent education in order to escape poverty. And in this country, a decent education requires a decent income.

Not having money to register at her first choice high school, Malaika ends up going to another school, and she was grateful that the school had proper facilities unlike the townships schools. The poor education and poor infrastructure that is common in townships schools inhibits the success of black pupils. In the past 20 years township schools have only deteriorated and some have shut down. Where I grew up in Kwazakhele, Port Elizabeth, about three schools close to my house have closed. The ones in operation, including the one I went to as a kid, are falling apart with toilets not properly working and sometimes with no running water.

Malaika’s mom valued education and she does whatever is necessary to ensure that her kids go to school, to the point where she worked herself into a psychiatric hospital. Whoever said hard work doesn’t kill, has never met black South African single mothers. It would seem that Malaika’s mother, just like my mother, took Nelson Mandela’s words to heart that “education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” These words have propelled me to aggressively pursue my education even in the hardest of times.

The one aspect in the book that left me feeling a little ambivalent was when Malaika Wa Azania was talking about being taught about apartheid by her family. I imagine that white young people are also getting a version of apartheid from their parents, and I am interested in how the white telling of apartheid would be similar or different from the black telling of apartheid. Although I think that apartheid history is important to teach and to be talked about, I am concerned about one-sided stories about the past from families. I wonder what this “family education” does because we need to be mindful of transforming South African society, and not create another generation of people who think along apartheid lines.

Malaika Wa Azania says that “merely by being born black in this country you had problems.” Malaika speaks to the ways in which our society is structured; that your blackness ensures that you are positioned at a disadvantage is South African society. Transforming this country is harder than people anticipated it would be in 1994. Memoirs of a Born Free is a book I want all my friends, my cousins, and my professors to read. This book is a reflection of our country told by a young black woman who is trying to find her place in the world and South Africans have so much to learn from it. Malaika Wa Azania chronicles the everyday struggles of young black people in the “new” South Africa. Malaika is the embodiment of Nina Simone’s “to be young, gifted, and black” and I am super excited that I live in a South Africa where young people like Malaika are taking their place.